Kermanshah is not the most attractive town, but our stay was enlightened by a few wonderful experiences, and a bas relief or two.

Just when we had made up our mind about Kermanshah, not a very friendly crowd here, very few ‘hello, welcom’s’, pushy people who have little with foreigners (one even managed a ‘fuck you’ in passable English), just when we had made up our mind, we met Behdad and Saba. In the street, while we are asking around to find a restaurant. They joined the conversation – as happens so often in Iran, somebody who speaks English offering his help to overcome the language barrier -, knew a nice place, and promptly decided they were going to eat there, too. Walked us to the restaurant, suggested some typical local dishes (which turned out to be delicious), sneakily paid the bill for all of us, absolutely refused anything about us inviting them instead, or sharing costs, insisted on showing us some more of the town, then went to buy icecream for all of us, drove to a park with fabulous view over the city by night, and only reluctantly released us late at night, but not after bringing us back to our hotel. The idea of us taking a taxi home was dismissed as ridiculous.

And that also sums up one of the biggest challenges in Iran: how to handle Iranian hospitality without abusing it. How to judge whether if someone invites you to their home, it is a real invitation, or customary politeness, called ta’arof, which is not to be accepted. Every taxi driver will, at the end of a ride, say that he doesn’t want to be paid, it is his pleasure to bring you here. But if you take this to litterally, he will be shocked, you just need to insist that you really want to reward him for his services, and after some time he will accept payment (and sometimes request quite a bit more than you had expected, or is reasonable, but that’s what taxidrivers all over the world are for). The people you share the taxi with, will insist you come to have tea at their house; they probably don’t really mean it, and would be highly embarrassed if you take them up on their offer. We have had people in the street, total strangers, inviting us for tea, for dinner, and for staying the night in their homes, but carefully declined their offers. But Behdad and Saba seemed genuine enough, and didn’t give us a chance, even, to refuse – you can hardly say ‘no, thank you, I don’t want to eat’, if you have just been asking about restaurants. They proved very pleasant company, too. And after they have been so generous, you don’t want to offend them by refusing their subsequent invitation.

So our stay in Kermanshah turned out to be another experience with Iranian hospitality and generosity. And we learn to get over our embarrassment, we learn to say ‘yes’, occasionally.

the most famous icecream shop in Kermanshah, no, in Iran (according to our friends…); people queue outside

Kermanshah itself is a vast city, perhaps 1 million inhabitants spread over an enormous area. As everywhere in Iran, there is an old covered bazaar, well-restored in this case, with several caravanserais – less well restored – inside. We happen to enter at the glitter and gold end, alley after alley with jewelry shops and kinky women’s dress (which remains well hidden underneath the outer clothing levels, more often than not a black headscarf and an all-covering black chador – Kermanshah feels quite conservative). Further on, the inevitable spices again, always a colourful element. The bazaar is full of people, yet, the atmosphere is different from elsewhere, everybody goes their own way.

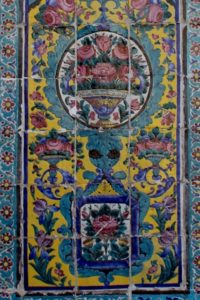

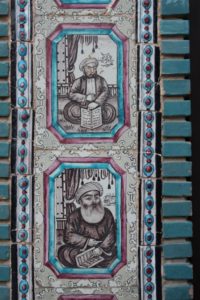

The Ehmad Dohla mosque, also within the bazaar, provides an oasis of peace, sharply contrasting with the busy corridors outside. The mosque, from the Qajar era, the dynasty that ruled Iran from the end of the 18th to the early 20th Century, is extensively tiled again, but like the Golestan Palace in Tehran (from about the same time), with many different patters, a bit chaotic on the eyes. Same is true for the Takieh Mo’aven ol-Molk, a religious building which is used during the mourning period Moharram as a theatre for enacting the battle of Karbala, where the prophet Hussain, the second of the 12 Imans that define the Shia faith, was massacred. Yet, here the tiling has more of an anecdotal purpose, showing several scenes of the battle, and of the life of Hussain. The building was closed, but after some negotiation – with the distinct impression, also fed by the variability of the ticket price during these negotiations, that any money handed over would disappear straight in the pockets of the negotiator at the other end -; after some negotiation we were allowed to briefly have a peek around. For free!

Just outside town is the alleged highlight of Kermanshah, the Taq-e Bustan. In and around two arched niches, carved out of the rock face, a number of bas reliefs depict hunting scenes and the coronation linked to several Sassanid Shahs (2nd Persian Empire), who reigned round about the 4th to 6th Century AD. They are remarkebly well preserved, and, although the site is actually pretty small, and you have seen it all in 15 minutes, make a worthwhile outing to the north end of town.

Less satisfactory was a visit to Bisotun, another site with bas-reliefs, some 30 km north of Kermanshah, from an earlier period, that of the reign of Darius, an Acheamenid ruler (1st Persian Empire) who had those made in 521 BC. The bas reliefs are no doubt impressive, but they are high above the ground, difficult to see in detail unless you have a good zoom lense or binoculars, with the view further hampered by extensive scaffolding. The other attractions, a boulder with a relief of the Parthian king Mithrades II and a much-restored statue of Heracles, are, let’s say, even less overwhelming; the empty rock face a little further, a smoothed area of 200 by 36 meters, was meant for another huge bas relief, but was never even started. But, we bagged another UNESCO World Heritage Site!

next: Shushtar