The traces and tombs of the Acheamenid Dynasty of the First Persian Empire can be found at Pasargadae, at the impressive site of Persepolis, and at Naqsh-e Rostam, all just north of Shiraz.

I have deliberately keept much of the Persian history out of this travelogue; with well over 3000 years it is obviously long, and quite complex. However, one cannot escape some of the basics, for the context, and that counts especially for the area north of Shiraz.

The First Persian Empire was that of Cyrus the Great, who between 559 BC and his death, at the battle field, in 530 BC, established the Achaemenid Dynasty. Cyrus was, of course, a war monger, otherwise you never get yourself an empire, and he conquered the then-known civilised world, from several Greek city-states in the west to the area around the Indus river in the east. But he was also, unprecedented at the time, merciful: his troops did not necessarily rape all the women and killed all the men. And another newbie: he was tolerant, allowed others to maintain their religion, didn’t force the Zoroastrian faith prevalent in the Persia of that time on those conquered. Two traits the world, and not in the least the present Middle East, could use as example, these days.

Cyrus built his capital in Pasargadae, of which little is left save a couple of columns representing various palaces and the remnants of a citadel. And a massive tomb, which stands majestically, isolated from any other rubble, on its own. Apparently, for most of history the tomb had been assigned to the mother of Solomon (a man who pops up everywhere, in the Middle East and Central Asia), but somewhere in the 19th Century a clever archaeologist suggested that a tomb of such dimensions, in old Pasargadae, could actually be that of Cyrus. And so it is. Very impressive.

After his death, Cyrus’ son Cambyses took over, and added Egypt to the empire. He died 8 years later, apparently from suicide after he was told about an uprising, not on the empire’s borders, but from within. The story goes that the leader of the revolt falsely claimed to be Cambyses’ brother. True or not, the revolt was put down a few months later by one Darius, who subsequently ruled, and further expanded, the empire – notwithstanding the fact that he does not seem to have been related to Cyrus’ bloodline. Which is perhaps why Darius went to great length to justify his coupe, in the rock carvings we have seen, from great distance, in Bisotun.

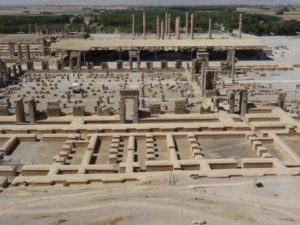

As emperors do, Darius built his own city, even more splendid than Pasargadae, in Persepolis (Persepolis actually being the name the Greeks assigned to it, City of the Persians). After Darius the empire struggled, not in the least because it fell back on the usual power broker attitudes – Darius’ son Xerxes succeeded him, but not before first killing his older half-brother. And not in the least because of the permanent war with the Greeks, a war that went on for another few centuries, until Alexander the Great destroyed the Achaemenid capital Persepolis in 330 BC. End of an empire.

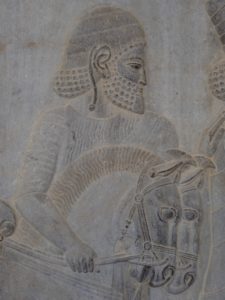

Well, except that the remains of Persepolis, despite its comprehensive sacking almost 2350 years ago, are still significant, more than just a few columns. Here you can still imagine the huge palaces and reception halls, designed to impress the envoys of subjugated provinces and tribes, who came to pay tribute to the emperor. Entering through the gate added by Xerxes, climbing the stairs to ever higher levels. These stairs, especially, are magnificent, carved with images of those foreign peoples, their characteristics, their typical tribute, and all very well preserved.

It is a pity that much of the area has been roped off, and you cannot freely wander around. But perhaps this is for the better: the site, especially Xerxes’ Gate, is adorned with graffiti from early visitors, 19th and 20th Century (and worse, an old man, Iranian, was scribbling his name on the side of the same gate whilst we were there, and nobody seemed to be bothered). It is also a pity that everywhere introduction videos are being shown, with the accompanying text blaring out over the entire site through huge loudspeakers – somehow, that undercuts the magic somewhat. Still, what remains of Persepolis is worth seeing.

Some of the Achaemenids have been buried in tombs above the site, but the main characters have been put in rock-hewn tombs nearby, at a place called Naqsh-e Rostam (once again, a case of mistaken identity, Rostam is a mythical figure from Persian history who gave his name to the location but turned out – perhaps the same clever archaeologist? – to have nothing to do with the tombs). The tombs are cut in a sheer vertical rock face, some 30-40 meters high up, and have been adorned with writings and bas-reliefs. Interestingly, on a lower level further bas-reliefs have been added, some 700 years later, by the early Sassanids, proponents of the Second Persian Empire, apparently in an attempt to associate themselves with what was, already in those days, considered the most powerful dynasty ever.

next: Yazd