Lebanon’s second city, Tripoli, is a great place to explore, wandering through the old souk in the city centre or along the harbour of El Mina. To get there from Beirut, one crosses once again a couple of centuries history, with examples of coastal Roman and Ottoman architecture and Crusader castles.

In order to get anywhere north of Beirut, one first needs to cross the Narh al-Kalb, or what was known as the Lycus River, an almost insurmountable river crossing in ancient times. Or so suggest the multiple inscriptions in the rocks along the river, of conquerors who did manage to cross, from Nebuchadnezzar to Napoleon, from the Romans to the French, who as recently as 1941 commemorated the liberation of Lebanon and Syria with an inscription here. These days a six-lane motorway will make you almost miss this major tourist site. The striking thing is, as Colin Thubron remarks in his 1967 travelogue of Lebanon, that every subsequent conqueror, unusually, judging by their behavior towards temples and churches, left the older inscriptions in place, without defacing them.

Just across the river are the Jeita Grottos, an incredible cave system, long as well as deep, with fabulous formations of stalactites and stalagmites, and all kinds of other intricate calcium-carbonate formations. The complex is, once again, tastefully lit: not like so many other cave systems that have mobilized the lighting of a fancy fair in bright red, blue and green, but full of soft lightning, earthy colours that blend very well with the rocks. The upper gallery is essentially a walk through the main cave, and the subsequent visit to the lower gallery includes a short boat trip on the underground river, less spectacular than the gallery above, but equally entertaining. The Jeita Grotto is presently being listed as one of the potential “new seven natural wonders of the world”, together with some 25 other sites, and people can vote for their favourites to be included in the top seven. You can imagine the campaign around this, lobbying going on for every possible vote, irrespective of whether you have the faintest idea about any of the other 24 sites or not.

Close to Jeita is the village of Zouk Mikael, a major tourist attraction with a re-modeled souk and a small Roman amphitheatre, heavily restored and clearly not so authentic anymore. The village itself is picturesque, and so is the small catholic church of, once again, Saint George, whose very hospitable priest opens the door for us and patiently explains the church’s history.

In the 1930’s Lebanon’s economy was dominated by silk, growing the silk worms and extracting the threads, dying them, weaving the stuff into raw silk sheets, and exporting it to France. It made up as much as 62% of the economy, and made a few people rich. Nowadays there is little left to show, apart from a small museum outside Beirut, where original tools have been kept, and some worms are still being raised on mulberry leaves. It is a lovely place, set is lush gardens, and visits are enhanced by temporary exhibitions. When we got there a collection of century-old silk carpets from a rich Lebanese business man was on display, and quite a collection it was!

Further traces of the silk industry can be found in the small towns north of Beirut, where the silk merchants built their houses. One of those is Jounieh, a small fishing village that was catapulted into the nightlife centre of Beirut during the civil war, when Beirut itself was obviously too dangerous to go and party. Long before this involuntary upgrade, the town was the center of silk commerce around, as illustrated by its old patricians’ houses that line the coast, allowing silk, and other export products, to be delivered at one end of the house, and loaded straight onto ships that landed on the beach at the other side. Many of the houses, in the traditional Lebanese style with three tall windows next to each other and small balconies, have been nicely done up, along the main road in the old center.

Above Jounieh, and connected by cable car, towers Harissa, or rather, the many churches and cathedrals of Harissa, situated on a mountain ridge and thus visible from afar. The most interesting, if not exactly beautiful, of them is the Basilica of Our Lady of Lebanon, a huge modern construction overlooking the coastal strip. The church has been designed by a Lebanese architect Pierre Al-Khoury, son of the first president of the country, in the 1970s – an amazingly modern design, for its time. The church is closed, somehow, it is already in need of restoration again, which is ongoing. Apparently, the idea of the design was to show, from high above, from an airplane window, the shape of the Cedar, Lebanon’s national symbol – although another story holds that the designs resembles a bird in flight, something admittedly easily confused with the shape of a Cedar, or a Phoenician boat, equally confusing. Outside the basilica is a huge statue of Our Lady of Lebanon, from where one has magnificent views over the sun setting in the Mediterranean, at the right time of the day.

Byblos is reputedly one of the longest inhabited places in the world, and if it always was as pretty as it is now, you can imagine why. Built on the coast, but against a steep slope, it has a number of old houses, and a beautifully restored souk – as everything in Lebanon very tastefully done, although the current shops are mostly tourist-oriented. New houses blend in with the old, and a tiny little harbor protected from the sea by a wall and a watch tower holds a number of boats, mostly for tourists, as well, I guess (there wasn’t much fishing equipment evident, anymore). It is almost a pity that there is also an extensive complex of Neolithic and Roman ruins, capped by a Crusader castle. The castle, largely recycling the Roman stone building blocks, is quite attractive, but for the rest of the complex one needs quite a bit of imagination, even though a lot of the Roman stuff has been restored, or at least rebuilt – not necessarily back to its authentic form, so is the amphitheatre apparently only a third of its original size.

In Amchit, a little further inland, we are back to the ubiquitous concrete apartment blocks, planted without any apparent structure. However, in between are hidden several old, well restored houses, each of them listed, each of them, apparently, privately owned. The old silk merchants have been replaced by other rich people, so much is clear.

In Batroun the small harbor is protected by a natural wall, that was later enhanced by the inhabitants. Here, too, are numerous old Ottoman houses, although not as ostentatious as in Amchit.

The motorway between Beirut and Tripoli is modern, fast and well laid out. The part to Tripoli is a few meters higher than the part to Beirut, on account of the mountain slopes. It characterizes the Lebanese mentality, though, that there are, every few hundred meters or so, stairs to climb from the upper to the lower section of the road, effectively institutionalizing the crossing of the motorway by pedestrians. Which indeed happens frequently. As are cars driving against the traffic, on the emergency shoulder, if there is any, otherwise in the rightmost lane. At least they drive fairly slow. And we also saw a cyclist on the motorway, with helmet and all, but that, I think, is indeed a rarity.

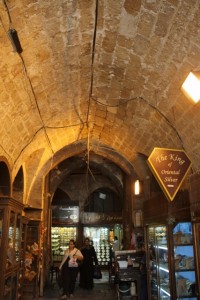

Tripoli then. The contrast with fast-paced, modern Beirut could not be bigger. Tripoli is traditional, and a little run-down. But at the same time the old town is a wonderful maze of small alleys and streets, one big shopping centre, but then in the form of a traditional souk, people selling from hole-in-the-wall’s, tiny little rooms under the vaults of the covered bazaar, or off the alleys in an old caravanserai. They are selling everything, from food and clothes – like the shop full of black burkas! – to furniture, gold jewelry, and locally made soap. Fruit sellers see no problem selling the fresh orange juice from under a Heineken parasol, or an Almaza parasol, the local brew here, despite the fact that in staunchly Muslim Tripoli there is no alcohol to be had, or at least not easily.

Tripoli’s Crusader Castle, towering over the city, is a lot bigger than the average Crusader Castle in Lebanon

In between all those alleys are mosques, madrasses – religious schools – and old Ottoman-era hammans – bath houses -, often of exquisite architectural design outside, with elaborately decorated doorways, in black-and-white stone. Inside, the mosques are not very attractive, but one of the hammans, now disused, had beautiful marble floors and marble fountains across a range of larger and smaller rooms, where you can imagine the men – always the men – sitting, plotting their business, or just plotting their family ties (indeed, maybe this is the same). Even though the door of the hamman was closed, someone with the key soon appeared mysteriously from nowhere, quite happy to drop his regular job to open the door and let me in. Or perhaps this was his regular job, who knows?

Above the old town towers the citadel, originally a crusader castle, later fortified by various subsequent tenants. The castle is being restored, and it is a bit of a mess, really, all together not very attractive, but it commands fabulous views over the old town, and also across the river to where the outer neighborhoods of Tripoli begin to rise against the slopes.

The harbour of Tripoli is known as Al Mina, with first the small fishing harbour, and further north along the coast the bigger port. It looks like boats are taken to sea at night, because at the end of the afternoon people are busy carrying baskets and nets on board, and filling jerrycans with fuel.

Just behind the harbour are streets full of old houses, and a caravanserai, fairly run down. We were looking for a reportedly very nice hotel called Via Mina, but we searched in vain, despite everybody in the neighbourhood knowing the hotel and pointing us in the right direction – we must have passed it at least three times without realizing, every time we were sent back from where we came from! Finally we found out that the hotel was now closed, or had reverted to a private house, or a special house for Lebanese VIPs only, it never became very clear. Bottom line, find another place. Which is not that easy, there is not much choice in Tripoli. In the end we settled for the vastly overpriced, and not particularly friendly, Quality Inn – an OK hotel, but not more than that, and with the enormous draw-back that it didn’t serve alcohol. I can imagine something like that in Arab countries, or Pakistan – although even in Pakistan foreigners can drink in certain parts of the better hotels – but in Lebanon this seems rather overdone, even if in Tripoli the more conservative Muslims dominate. Certainly, the television in the dining room was not censored, and showed a rather scantily clad anchorwoman on a Lebanese talk show. Anyhow, no choice, really.

Just on the other side of the Al Mina peninsula is the local Corniche, lined with old and battered VW vans, and some other contraptions, which are being used as shops to serve coffee and nargile, the hookay or water-pipe, which is smoked everywhere in Lebanon. Some 30 or 40 years ago especially the Christian part of the country looked down on this habit, seen as a primitive Arab thing, that refined Christians wouldn’t touch; but you see, if it tastes nice, prejudices can easily be overcome. In Beirut the nargile is cool, and you see many young people, men and women, smoking in trendy cafés. Here in Tripoli, the chairs and parasols on beach in the late afternoon and evening is the place to be; and the taste of the tobacco can be washed away with a fruit juice or a coffee.

Continue: The Mountains and The Valley