Accra

At breakfast we find out that Ghana was a British colony. Eggs, sausage and beans, on toast. Gone are the delicious baguettes of former French colonies!

Alonso has relented, and we now have a full day in Accra. With my usual planning skills I have set out a walk along the most important highlights, total walking time some one-and-a-half hours, piece of cake really. The nearest spot, Osu Castle, the former Danish stronghold and slave trading centre, is 15 minutes from our hotel. Right! Halfway we take a break in a park under some trees, it is sweltering hot, already at 9 am. When we finally get to the castle, half-an-hour later, it is closed. Just this week.

A little further on is the Black Star Arch, the Ghanese independence monument, and Black Star square, a gigantic parade ground, with coloured stands on three sides. Not very pretty, but at least we have seen something. Important, because our next two targets, the Artisan Collective and the Kwame Nkrumah memorial, for the first post-independence president, are both also closed. We give up on the plan, and spend an hour in the Vodaphone office, instead – airconditioned! -, trying to get a local sim card. But for this you need to be registered, and despite many attempts, registration fails. We also give up on the local sim card. Refreshed from the AC, we walk into the direction we think is best.

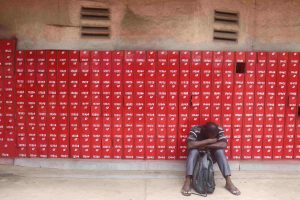

And that works. Ten minutes on, exhausted again – it is really hot! – we find a balcony terrace for a drink. It is closed. But, Ghanese people being so much nicer than many of the people we have come across, so far, the owner, who is working on the electricity of the bar, says “just relax, what would you like, we will get it for you”, and then sends somebody onto the street to find a cold coke and a cold sprite. This would not have happened in any of the earlier countries we have been on this trip, perhaps with the exception of Chad. In the mean time we have a nice, elevated vantage point from where we can, undisturbed, take some pictures. Because the one thing that hasn’t changed is the photo paranoia, although perhaps business model is a better word. You have to ask permission first, and more often than not, you will be asked to pay first. Even if I would want to pay, it would ruin the photo, because all the spontaneity would have quickly gone, people posing, instead. The opportunism of the model is further highlighted when I take a picture of a building. Somebody passing angrily yells at me that I need to ask permission. Permission from a house? Admittedly, when I confront him with this, he actually thinks about it, and agrees that that is not necessary. And it goes like that so often. But it is so tiring. It takes the fun out of taking photos in the first place.

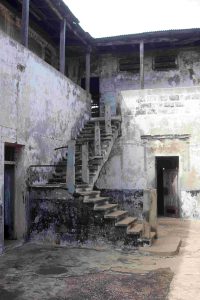

Our random program brings us to the Ussher Fort, an initially Dutch facility from the slave trade times. The word ‘fort’ is misleading, this is not a fort, this is a warehouse, with lots of rooms to keep slaves, until the traders came to pick them up. The building is not noticeably restored, which adds to the drama. Of course we have all heard about slavery, of course we all abhor the idea, but seeing its facilities like this makes it so much more realistic. Room after room, with sometimes up to 200 slaves tied to rings in the floor, the original doors shut, the stairs through which they were led away, the so-called ‘point of no return’ – which means that from there on they were not the responsibility of the land-based trader anymore, but the ship owner.

From the roof, where the slaves must have seen their transport for the first time, having no idea what was happening to them, we view the harbour, full of fishing boats. And full of activity on the beach, where food stalls sell their wares, whilst at the far end the rubbish is piling up along the slope. Handling of trash is not one of the strong points in Africa.

In the next fort, the originally British Jamestown Fort, the meaning of ‘point of no return’ is even more poignantly visible. In addition to the large rooms and the slave market place inside the fort, there is a smaller compartment outside the ‘point of no return’, where slaves were kept who had been sold, but for whom was no place onboard anymore, they had to wait for the next ship. Most of those didn’t survive the waiting, and – according to our guide – were then fed to the vultures. Interestingly, our guide doesn’t put all the responsibility on western traders, he also recognises that the slave-raiding African kings played an important role in the process, “selling their own people”.

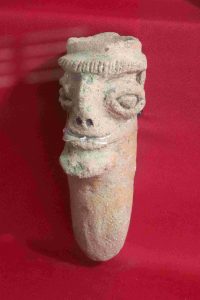

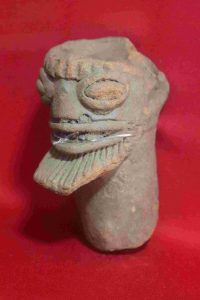

and this is a funerary figurine, accompanying an elite community member in the grave, following Akan tradition

After the sobering experience of these two forts we take a taxi to the National Museum, which, for a change, is open. It is a small museum, but nicely done, following the history of the Ghanese from what they call ‘the beginning’, some 4000 years ago – and represented by a series of real nice terracotta sculptures – to present day. Without the slightest critique, stressing the peace and harmony in which Ghanese people live together, have always lived together, really. Hmmm. Perhaps they should have consulted our guide.

Next: on the way to Elmina

Closed, closed and closed but at least the National Museum was opened but it didn’t tell you the stories of you guide and what you have seen before.