The ‘Scramble for Africa’ in West Africa.

Somehow, things changed in 1879, the year France decided on an expansion policy in Senegal. With the abolishment of the slave trade another economic model had to be developed, and in this case is was groundnuts. But these grew in the African interior, outside the immediate control of the French. Where earlier some French citizens occupied a number of trading ports along the coast, in 1879 the official policy changed towards full scale colonialisation; and it was subsequently left to the military men to arrange this.

In the course of the many military campaigns the French objective shifted, from a focus on creating a viable colony in Senegal, to joining French territory – linking what had now become French West Africa with French-occupied Algeria in North Africa and the French Congo region in Central African – and turning this into a vast French state in Africa. To achieve this, conquering the area around Lake Chad was critical. But look at the map, and you see that by the end of the 19th C they had been pretty successful. Yet, their strategy was quite unusual for the time. Whilst most colonial expansion at the time was done by treaties, to try to dominate and control existing trade, in West Africa the French went in with full military force conquering territory, hoping the trade would follow.

Initially, the British maintained their reluctance to colonise, even though there was, already since the 1830s, considerable commercial interest around the Niger delta. Long before this area would gain notoriety because of its vast crude oil reserves, the delta was already known as the Oil Rivers, on account of its importance for the palm oil trade. In the beginning the Brits traded with middlemen, who carefully protected access to the palm oil further inland, but increasingly, traders would sail up the many branches of the delta to access the oil directly from the source. But competition was killing, and ultimately one man, Sir George Goldie, managed to buy out all the English merchants, and then the French, too, to create a monopoly with what he called the National African Company. We are talking 1884 now.

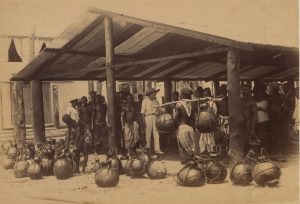

Palm oil market: Igbo men in the Oil Rivers area of present-day Nigeria bring calabashes full of palm oil to sell to a European buyer, c. 1900 (Image © Jonathan Adagogo Green / The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY NC SA)

Palm oil extraction: The new stamping method of extracting palm oil, depicted in this 1845 watercolour, often involved slave labour (Image © Édouard Auguste Nousveaux / National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London)

Goldie was keen to establish a new British colony, but the government was still not very willing. They did recognise the French threat, though, so reluctantly they instructed their local consul in the Niger delta area to agree official treaties with African rulers, which would supersede the commercial contracts of Goldie, and similar commercial interest around the Lagos area. A move more to keep others out then to get heavily involved themselves. However, they hadn’t anticipated the initiative by Bismarck’s Germany, who came late to game. A German tug of war had been despatched early 1884, to the West African coast, with a consul who managed to agree treaties with Togoland and Cameroon before the British got their act together, securing these as colonies for Germany. Which was all confirmed in the Conference of Berlin later that year, where representatives of the European powers and the USA agreed on a framework for colonisation of West Africa (in this case all the way down to Belgian Congo), including recognising the current state of affairs, ie the sovereignty of the European powers over their respective African territories. There were no Africans at the Conference.

So by the end of the 19th Century this left West Africa divided up by France, Britain and Germany, with the occasional oddity of Portugal holding on to what is now Guinea Bissau and Spain occupying Equatorial Guinea, further south. Oh, and the Americans had, in the meantime, created a colony for the repatriation of freed slaves, called Liberia. Another oddity, which gained independence in 1847. The Dutch, Danes and Swedes had abandoned West Africa as soon as the lucrative slave trade was abolished.

And with the exception of the German colonies, which would be divvied up between France and Britain after the First World War, it would stay this way until the 1950s and 1960s, when independence beckoned.

By the way, I cannot say this often enough, but the above two entries are a huge simplification of what really happened in history. I will include several books on the reading list, later, if you want to get the full story.

next: just before departure, a look a Chad, our first stop.