At the end of almost three years living and working in Tanzania (1987-1989), I took two weeks for a short trip to Zimbabwe and Botswana. A fabulous experience, of which unfortunately, I took no notes, and only a limited amount of photographs – this was the analogue era of photography, in which you were still limited by the amount of film rolls you carried. So what follows is a no doubt incomplete, and quite possibly inaccurate account of that trip, based on distant memories and discoloured, scanned slides. Still, worthwhile including here, I think.

Harare

The capital of Zimbabwe was, at the time, a small town, quite orderly and organised. Things worked, there was good public transport, and other facilities. Although the country had been independent for more than 20 years, and majority black-governed for almost 10, some old colonial tendencies prevailed: when I entered the bar of a posh hotel, I was asked to put on a tie and a jacket, and when it transpired that I had no such attributes with me, I was allowed to borrow this from the wardrobe, which was specially kept for this purpose.

The most impressive element of Harare culture was the Shona sculpture scene. Several upmarket galleries exhibited and sold the most fabulous stone sculptures from Zimbabwean artists, made in a variety of styles from often brightly-coloured ‘soap stone’ (real name?). But the success of some famous artists had also bred a whole range of followers, who produced anything from cheap tourist stuff to quite accomplished works of art, which were being sold in lesser galleries, or along the streets. In the end I bought only one piece, an owl where the artist had made brilliant use of the outside oxidised properties of the rock, creating reddish wings on a green body.

a game park

The photos prove that I also went to see a game park in Zimbabwe, but I cannot remember which one it was – definitely not the Huangwe National Park, the country’s biggest. What was special, compared to the game viewing experience from three years Tanzania, was that in Zimbabwe had many more rhinoceros, not only the ‘black’ variety that we occasionally spotted in Tanzania, but also the rare ‘white’ one (equally dark grey coloured – the difference is in the upper lips).

Great Zimbabwe

The Sub-Saharan part of the African continent is not rich in ancient stone structures. Great Zimbabwe is the notable exception, believed to have been constructed from the 11th Century AD onwards. The most eye catching elements are the Royal Enclosure (Great Enclosure), with walls up to 11 meters high and 5 meters thick, and the Conical Tower, an 9 meter high structure inside the Royal Enclosure, of which the meaning and role remain enigmatic. A lot else also remains a mystery, like the reasons for its demise in the 16th Century; perhaps due to climate change, or the exhaustion of local resources. In the same complex are more structures, one of which is the Hill Complex, reached by stairs in between solid rock: a perfect defence mechanism, I would think.

Almost predicably, the early European colonisers couldn’t believe that such a structure had been erected by black Africans, so speculated on a Portuguese, or even a Carthagian origin, a view that was maintained even throughout the early years of independence, under Apartheid-style white rule. By now, it is widely accepted that this is indeed a pre-colonial construction, build by the ancestors of the Shona people, the now-dominant tribe in Zimbabwe. In fact it is only the largest of some 200 similar compounds in Southern Africa, except that these are much smaller and often less well preserved.

When I visited, in 1989, it was misty. Which created a spooky atmosphere, somehow quite fitting for this impressive, yet mysterious monument.

Khami ruins near Bulawayo

Bulawayo is one of Zimbabwe’s oldest towns. It was – and no doubt still is – even smaller than Harare, although its main roads wouldn’t seem so: they were built so wide that a horse-drawn wagons could turn in one go (horses not having a reverse gear).

The main attraction in Bulawayo, for me at least, were the Khami ruins, second only to the Great Zimbabwe ruins. Khami is slightly younger than Great Zimbabwe, originating in the 15th Century, and abandoned 200 years later, when it was ransacked by other tribes. The constructions included several platforms, walls and cattle pens. Many of the walls were intricately decorated with geometric patterns. Within the complex, I remember, you could identify the relative age of the constructions, the most perfect walls being from the heydays of the kingdom, whilst the later walls were much less carefully constructed, with large variations in block-size, for instance.

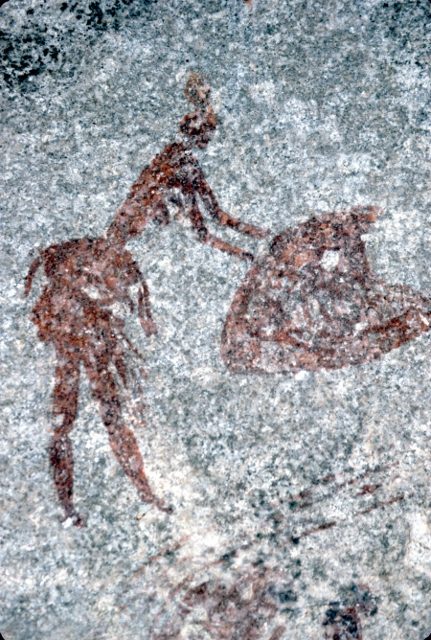

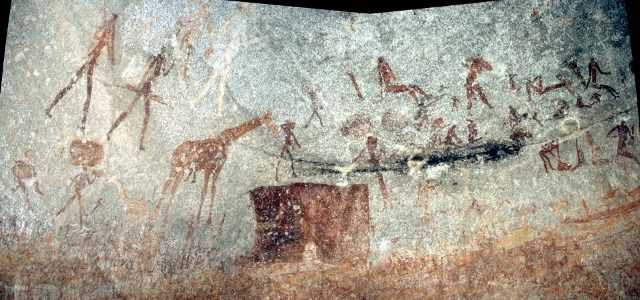

the rock paintings

Another unexpected, but very interesting Zimbabwean attraction are its rock paintings – at the time not mentioned in any of the guide books I had, and not signposted anywhere. Obviously, rock paintings were not considered part of the national heritage, they were not from the dominant Shona tribe.

Actually, it is now firmly established that Zimbabwean rock paintings are of San origin – bushmen -, who have left Zimbabwe territory at least a thousand years ago. Which makes them unique, because San paintings elsewhere in Southern Africa may have been painted as recently as less than 100 years ago, or as early as 10,000 years ago, they are notoriously difficult to date.

One of the richest rock painting sites are the several caves in the Matobo Hills, south of Bulawayo. I remember finding some kids in a local village to show me the way to, first, the so-called White Rhino Shelter, my first real rock painting experience (except for the rather primitive paintings in Malawi), scrambling up a fairly steep hill. Not having expected the artistic finesse, the wealth of subject matter, the bright pigment colours inside the dark cave, I was immediately sold. And not only because of the paintings; there was something magic in looking out over the plains below, from the high vantage point in front of the cave. Imagining that others would have sat here a thousand years ago, seeing exactly the same.

for more pictures of these exciting paintings look in the individual entries, of Silozwane Cave and of Nswatigu Cave and of Pomongwe Cave,

I spent a full day seeking out more caves with San images in the Matobo Hills, once again mainly aided by young kids. The average adult Zimbabwean couldn’t care less about these fabulous treasures. I found three more locations, Pomongwe Cave, Silozwane Cave and Nswatigu Cave, full of exciting images, of animals and hunters, and sometimes of domestic scenes. Unfortunately, I spent far too few film rolls on photographing these. But I also vowed to come back to Southern Africa, to see more of this unique and exciting art form, which for obvious reasons you won’t find in any museum.

Victoria Falls

No visit to Zimbabwe is complete without a visit to the Victoria Falls, locally named Mosi O Tunya – ‘the smoke that thunders’. And walking around the area, that is exactly the impression you get, for much of the time you only see a cloud of water spray, and hear this incredible noise. Until you reach the falls, and are suddenly confronted with a mile -wide river that somehow disappears in a narrow gorge of the Zambezi River over a hundred meters lower. Spectacular, of course, and spine chilling, as you see lots of local people walking across from one side to the other, just above the falls, to Zambia, in fact.

beautiful pictures Bruno, brings back memories !

Peter.

ah, dat is waar, jij bent daar ook geweest. En daar heb je nog wat dead wood van meegenomen, kan ik me herinneren. Wellicht eens ruilen, voor een lekker flesje wijn?