Argentina, including its Mesopotamia, has prepared itself with all forms of nationalistic symbols for the football Worldcup

In December 2022 we travel through the Northeast of Argentina, exploring not only the national parks El Palmar and Esteros del Ibera – with lots of wildlife, especially birds -, but also the hypermodern Yacyreta hydroelectric complex and the 18th Century Jesuit ruins of San Ignacio Mini. Our tea excursion around Obera is being cut short by the demands of the Football Worldcup, and along the way we observe Argentina as it is, both the good and the bad.

With one of us being Argentinian, we do come to this country regularly, to visit family and friends, but because of the recent Covid pandemic, our last visit was actually almost four years ago. In between the social commitments with family and friends we find a week to tour some of the country, and not wanting to go too far away from Buenos Aires, we opt for what is called Argentinian Mesopotamia. This consists of the three provinces in the northeast of the country, Entre Rios, Corrientes and Misiones, wedged in between the Uruguay and Parana Rivers – the rivers that ultimately merge in the Rio de la Plata, Buenos Aires’ waterfront.

El Palmar National Park

We have a number of targets, one of which is to try to see at least some of the matches of the 2022 Football Worldcup, which is being played at a variety of times during our trip (and before and afterwards, of course, something like that doesn’t fit in a week). The first geographically defined target, however, is the Parque National El Palmar, in Entre Rios. We enter the province by crossing the impressive bridge across the ‘brazo largo’, the big arm, of the Parana River, a little later followed by the second, equally impressive bridge. After this, along the way the scenery doesn’t change much, but it is a lot emptier than where we come from, Buenos Aires province. Mostly flat land used for cattle ranches – the ‘estancias’ – and to a lesser extend for grain production. Yet, especially the grain silos are impressive constructions, ever bigger, ever more modern, it seems.

The reserve, at some five hours drive north, is quite small, 85 ha, located on the banks of the Uruguay River. It was established in the 1960s to protect the Yatay palm tree, a tropical palm species most common in South Brazil, that threatened to disappear from Argentina at the time. No more! The park is full of them, and even outside we already spot the first examples. At the park entrance we need to register, complete with ID card, the number of which is written by hand in a log book. Why on earth this is necessary, beats me! For sure nobody is going to check this later on again, but who knows, perhaps it is a form of providing work. It isn’t the first time, and won’t be the last, that I question the efficiency in Argentina. But everybody is very friendly, pointing us in the right direction – there is really only one road, to the river bank, and a few dead-end diversions. On the way, we don’t only spot the capybara, the largest rodent in the world, apparently, but also various colourful birds.

At the river side is a restaurant, a welcome distraction after five hours drive, and there is a walking path to a small beach, which also passes a historical site. This turns out to be a kiln that was used for the production of lime, from the end of the 18th Century. Not the most spectacular of historical sites, and its importance lies perhaps more in that this was the first industrialization attempt in this area. But the kilns were being abandoned again as early as 1825, and it took until the 1950s before further buildings were being constructed, with an even shorter life span, because 10-15 years later the park was established.

Esteros del Ibera

After an uneventful night in Concordia, where we caught the last 15 minutes of the last match of the day, and where we had the worst pizza ever, we make our way to Colonia Carlos Pellegrini, a village on the edge of the main lagoon of the Esteros del Ibera. This is one of the largest wetlands in the world, a combination of swamps, bogs, stagnant lakes and lagoons.

We cross the ‘border’ between Entre Rios and Corrientes. Argentina is a federal republic, and individual provinces have substantial power, but I am surprised to find controls between the provinces. Not real border control, of course; here, at least, we don’t have to show our IDs. But trucks are being checked, and I don’t know for what. Other than some form of ‘direct taxation’, as I used to call this. Come to think of it, you would imagine that the border patrol, as well as the many police men involved in random traffic controls along the motorway, in which many cars are being stopped, would have better things to do. But no, we, too, are being stopped, and fined, because we forgot to switch on the car lights. A major infraction! As I am not the one driving, I was not privy to the subsequent discussions with the officers, but I understand that they were keen to come to ‘some kind of settlement’, which would have been less that the official fine.

Soon after, we turn off from the main motorway onto a smaller road, to the town of Mercedes, where we have lunch, while watching one half of a football match. After this, it is onto an unsurfaced road, ‘ripio’ in local language, to the park office. Esteros del Ibera is also a nature reserve, in fact it is the largest reserve in the country. But even outside the park we already spot our first wildlife, more of the capybaras, a fox who is too fast for our cameras, and several deer. Another common sight is the nandu, officially called the Greater Rhea, and much like an ostrich. With all these distractions, and with the park officials once again wanting to have all our ID details, we arrive way too late in our comfortable lodge to see any of the remaining football.

But we are well in time for our first park walk, with one of the guides of the lodge. Nicolas turns out to be a quiet, but very knowledgeable guide, who also seems to know exactly where he can find animals. He brings us to the monkeys – no idea whether these are always in the same spot, but that doesn’t matter. We see several deer, again, and some birds. And we have a very enjoyable walk through jungle-like forest interspersed with savannah. Partly across wooden walkways, which are designed to keep your feet dry, although today there is no need, the water levels are very low.

In the next few days we make several boat trips – at least there is still enough water for that! – across the lagoon, through insignificant streams, or through canals connecting small lakes, all equally wonderful experiences. We get close up to crocodiles, lots of them, there are more deer to admire, and there is an incredible variety of birds, in all colours and sizes. I am not a expert, I just like to see birds for their colours and for their grace, either hopping around or flying. Believe me, I got much to enjoy during these boat trips. For even more pictures of the birds, go here.

And even when we are not in the boat, or walking the trails, we have a lot to see, around the lodge. To the nearby jetty, or along the lagoon shore, or simply observing the trees, around the swimming pool and the restaurant, or just sitting under the veranda of our cabin. There are birds everywhere, and most of them are quite used to people, it seems, not at all scared.

Oh, and in the shared living room, with big television, we see both our football teams, The Netherlands and Argentina, qualify for the next round.

The Yacyreta Dam

After a few days we leave the Esteros del Ibera behind, and make our way further north. We drive more ripio road, along the edge of the park. And although there is still some cattle ranching here, with large estancias – incredible, at several hours drive to the nearest town -, forestry is taking over as the dominant business model. We are getting more into sub-tropical climate, and pine trees and eucalypti are two popular, fast growing species that do well in this area. Plot upon plot are planted, in neat rows. And we will keep on seeing this, and the many processing facilities that turn trees into useable wood and pellets, until far into Misiones, the next province.

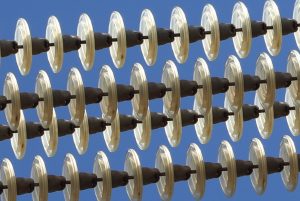

But just before we leave Corrientes, we have one more target to visit. Near the town of Ituzaingo is the Yacyreta dam, linked to a huge hydroelectric plant, and blocking the Parana river in two places. The largest of the two dams is some 800 m long, and contains 20 turbines that together have a capacity of 3100 MW. To put things in perspective, this makes the dam the 32nd largest in terms of capacity, in the world – a list which is dominated by large Chinese dams, of course, the Yangze River dam with 22,000 MW capacity being by far the biggest. Incidentally, the second largest, the 14,000 MW Itaipu dam at the Brazilian-Paraguayan border, is also in the Parana river, further upstream. Another interesting statistic is the annual production, Yacytera delivering some 20 TWh, on a total consumption in Argentina of 125-130 TWh/year. Although part of the production goes to Paraguay, which is joint venture partner across the river, most of it is being used in Argentina, which illustrates the importance of the complex.

For the free tour of the dam we need to register at the company’s office in Ituzaingo, once again with IDs. Perhaps this time slightly more justified, as we are actually travelling into Paraguayan territory. In a bus, together with perhaps 10 or 12 others, and a guide. In the next one-and-a-half hours we are being shown the dam complex from different sides, which is actually very impressive. There is a 23 meter difference in height between the lake behind the dam and the river bed downstream, there are sluices to allow boat traffic to pass, and there are the 20 turbines, one of which is being shielded off from the water flow by a huge metal sheet, for maintenance; there are even fish ladders to facilitate the passage of fish that spawn upstream. And we are presented with a huge amount of numbers and statistics, most of which don’t mean much to me.

Of course, the guide tells us a lot less about the controversy that the dam created, when it was first proposed in 1958, or when construction started in 1983. The lake created by the dam is well over 20 meters higher than the original river, covers 1600 km2, and displaced 40,000 people. A census in 1990 was secretly altered to reduce the amount of compensation that had to be paid. Biodiversity was lost, and local climate was affected by the large body of water. And, obviously, the original construction budget was spent several times over, financed by foreign loans that Argentina could ill afford – but enriched lots of people associated with the project. Not many commentators expect this ever to become an economic success, certainly not enough to offset the ecological disaster. But, impressive it is, for the casual visitor. Well worth missing a football match or two.

San Ignacio Mini

One of Argentina’s most famous man-made tourist sites are the ruins of San Ignacio Mini, in Misiones. In the 16th Century several Catholic orders despatched missionaries to the Portuguese and Spanish colonies in Latin America. The Jesuits came relatively late to the party, and established themselves, with the approval of the colonial authorities, in the still underdeveloped area around the Parana River, in what is now Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. They set up ‘reducciones’ – reductions -, usually consisting of a church, a monastery and a string of houses and workshops, and invited local Indian families, the Guarani, to come live at the mission. In the process, the Indians were not only being introduced in European ways of thinking – and not in the least, believing, of course – and ways of working, learning useful, productive skills, but they were also protected from slave raiders operating from Brazil. The Jesuit reducciones have been criticized by some, but most people would agree that they were relatively sanguine communities, with socialist characteristics and significantly benefitting the local population – unlike in many other colonial institutions at the time.

There are several reducciones in the province of Misiones, and across the border in Paraguay. The best preserved one is the complex San Ignacio Mini, a mission originally set up in 1610, but moved to its current location in 1696. It was called Mini, to distinguish it from the larger mission in Paraguay, Guazu (which means ‘great’ in local language). As with all the Jesuit missions, it fell in disrepair after the expulsion of the Jesuit order in 1767, when the Spanish king decided that Spain needed to assess more of its authority on its American colonies. The remaining buildings were further destroyed in 1817 by Brazilian forces in a local war, and subsequently disappeared under dense overgrowth, only to be rediscovered again around the turn of the century. Yet it wasn’t until 1940 that the Argentine government started with the rehabilitation of the complex, now a major tourist site, and recognised on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

From the ticket office, where we once again need to register our ID cards – what is this, obsession with writing down all this useless information? – we are shown into the museum, and then past a later building, to the main plaza. Initially, we find ruins of houses, including those of the columns that would once have supported the roofs of the verandas, on both sides of the path. Soon the main plaza opens up, with at the other end the remains of the church, a large building made of red sandstone. Crossing the plaza, we admire in close-up the carvings around the arches of the two entrances. Inside the church ruins, the building turns out to have been surprisingly large, some 25×75 meters, with side entrances equally delicately carved. There is no roof anymore, but most of the walls are standing upright – restored, no doubt, but impressive nevertheless. Towards one side the construction continues to what used to be the educational centre. Here, dark basalt form the dominant building blocks, with the softer, more easily workable sandstone only used for the window and door frames.

Outside the church and the school building, we wander around a bit more, looking at the ruins of more houses, and the old water well, but also the flowers, the trees – quite sizable, yet postdating the construction: wood grows fast here. Apart from the occasional tour group there are very few people; the atmosphere is tranquil, peaceful. Almost a pity to leave the place again, after some one-and-a-half hours.

There are several other Jesuit ruins in the area, and I do not necessarily have to see them all. The local tourist office recommends the Corpus Christie site, in the nearby town of Roca. Where we are confronted with the other extreme. A museum shows a maquette of the former ‘reduccion’, complete with church and plaza, and numerous buildings. But when we subsequently walk the path through the jungle, following a route through the presumed ‘reduccion’, there is not much to see, except occasionally a sign board with a drawing of how it may have looked from that specific location. The only traces left are a few building blocks and the remains of the stairs to the church. One needs a lot of imagination, or an extreme amount of enthusiasm, like the two people who work here to receive tourists – and who do need to write down the numbers of our ID cards, of course. The only tourists coming here must be those referred to by the tourist office, but really, there is nothing to see. Come to think of it, this may have been how San Ignacio looked before its restauration.

The tea country

We stay in Misiones, but a little further east, where around the town of Obera Argentina’s tea estates are concentrated. I love tea country, especially the colour of it, so we had planned a day visiting various estates, with guided tours and trying the local produce. Unfortunately, we got caught up by conflicting interests, and had to choose between the day-long tour, or just a short drive through the country side, followed by watching two football matches in front of a large television screen in our hotel. We chose the latter, as in one match The Netherlands played, and in the other Argentina.

The drive through the tea area proved nice enough, although the tea plants had been cut very short. It looks like we missed the spring harvest, or possibly the second harvest, too – had we taken the tour, we would have learned. But not only tea is grown here, also ‘yerba mate’, that quintessential Argentinian (and Uruguayan) herbal drink that people share with family and friends through a communal cup and straw, as a social institution as much as a thirst quencher. The leaves – which look like tea leaves, we checked! – are dried and put in the cup, after which hot water from a thermos flask is added, and again after drinking, or rather, sucking it through the straw. I don’t particularly like the bitter taste, but my travel companions devour it, time and again. The mate plants look somewhat darker, and much larger than the tea bushes, that much we find out even without a guide.

Later, in Obera, we see both our teams succeed in what is the first round of the so-called knock-out phase. The Dutch win goes almost unnoticed, but the Argentinian one is as if they have already won the Worldcup; within minutes the streets fill up with people, motorbikes, cars hooting and displaying flags from each and every window, pickups full of people in white and blue shirts. These people are not yet concerned about the next match, unlike we ourselves – we know that we will now play against each other….

The long way back

And now for the hard work. It has taken us the best part of the week to reach where we are, well over 1000 km from Buenos Aires. This is a big country, after all! There is no time anymore to visit the biggest tourist attraction in Misiones, the Iguazu Falls all the way north at the intersection of the Argentinian, Brazilian and Paraguayan borders. In any case, we have all seen these before. Instead, we have two days to get back.

The first one involves nine hours’ drive, 750 km, crossing from Misiones into Corrientes and then into Entre Rios. Spending the whole day driving, the presence of officials along the road is even more staggering. Indeed, two times we cross a provincial border, and I count no less than six police controls along the way, of which we are being stopped at four, and of which we are being fined at one. Lights again. The police man says that this is indeed a major infraction, and the only thing left to argue is about how to settle the fine. Apparently, this is a fully accepted state of affairs, in this country. But you would think that most of these people would have something better to do, on a Sunday?

Positive highlight of the day is the shop Maria Regionales, which we already saw advertised on the way up, with the promise of lots of delicious regional products. For several kilometres the side of the road is covered with advertisements, every 100 meters or so, for escabeche de berenjena (pickled aubergines), or pickled red peppers, pheasant, deer, buffalo, anything you can think of. They have queso casero (homemade cheese), salamis, jamones (ham), and lots of other fabulous treats, all locally produced. Reason enough to take a break, and collect a variety of pots full of delicacies.

We stop in Colon, a small town on the Uruguay River, with a not unpleasant water front and a wonderful old-fashioned hotel. We have our last feast on river fish, with exotic names like surubi, boga and pacu. And then, the next day, we drive back to Buenos Aires. As soon as we cross the ‘brazo largo’ again, we swap the emptiness of Argentina’s Mesopotamia for the buzz of Buenos Aires province, and a little later the city itself.

And we brace ourselves for the upcoming football match.

After this wonderful trip you are in time in Buenos Aires for the final footballmatch.

It must be a great atmosfeer in Buenos Aires with Argentina in the final match.

I hope they will be the champions so both of you can have a big party!

Enjoy your stay.