Unusually, for this site, this is about a country I never visited, a trip I never made. About regrets, missed opportunities. Or not, perhaps! Read on. Obviously, the photos are not mine, I found them on the internet, and have credited them where I still remember.

the map

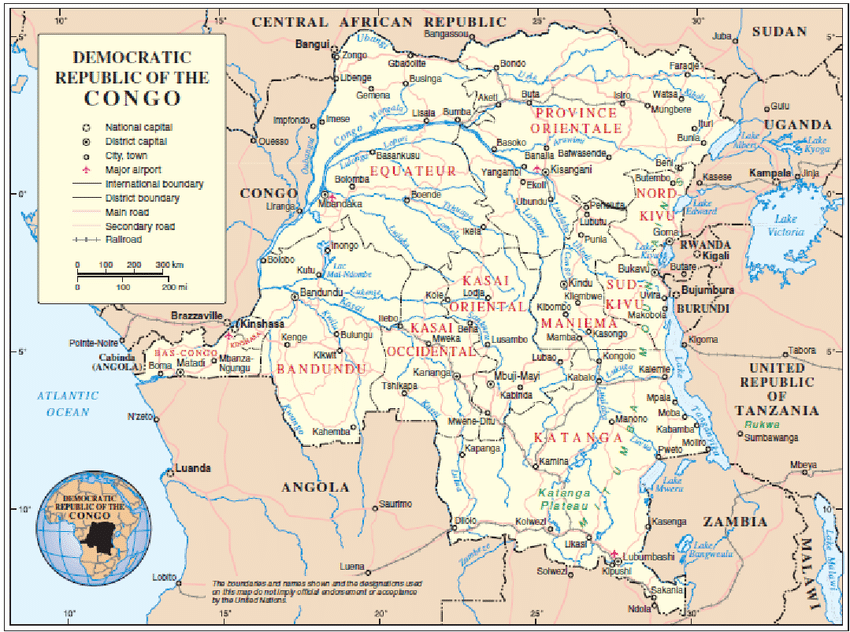

I am fascinated by maps, and I love studying them in great detail, a hobby that more often than not generates lots of travel plans – admittedly, some more realistic than others. The Democratic Republic of Congo, the country that was known to me in my younger years as Zaire, has always been an attractive one from the map’s point of view. It is gigantic, covering the western half of Africa from Lake Tanganyika to the Atlantic Ocean. More importantly, it has the Congo River, which curls some 4700 km through much of the country. The upper most reaches of this river, originating in the mountains of the East African Rift system, may be in Zambia, but for all intents and purposes, the river runs its length through one country only, the Democratic Republic of Congo. First to the north, then bending west and further south, to the capital Kinshasa, before it turns west again and empties into the ocean. A fabulous travel opportunity in a country that has hardly any roads – I thought.

The first time this idea presented itself was during some of those ‘younger years’, when I lived in Tanzania in the late 1980s, and travelled as much as I could in the region. I didn’t know much about Congo – Zaire, then -, except that it was then ruled by a dictator called Mobuto Sese Seko, the man with the leopard hat (on every official photograph he was seen wearing a hat made of leopard skin, his way of demonstrating his commitment to the African heritage). Mobutu was a rather brutal dictator, but in the days of the Cold War, that was of subordinate importance. Equally, the fact that he is the man who defined the idea of a kleptocracy, seeing little difference between the state’s finances and his own, didn’t count for much in international politics. He was on the side of the West, and that was all that mattered. Oh, and the country was relatively stable, then, or so we thought. But I didn’t travel down the Congo River in my younger years, of course not. For starters, I had set my sight on traveling overland back to Europe, through Kenia, Sudan and Egypt, but even that didn’t work. Something to do with employers who expected me to turn up for work again, after a few weeks holidays. And when I did get back to Africa, it was for a trip through Namibia and South Africa in 1991. After that, the rest of the world was beckoning.

the idea isn’t going away

(source: https://kumakonda.com/)

However, the idea of the Congo River trip never left me, and occasionally I came back to thinking about it. But first there was the civil war, rebels from the east of Congo marching up to the capital Kinshasa, and overthrowing the Mobutu regime. The country wasn’t so stable anymore, and it got worse. Ever since, there has been a war in Eastern Congo, at some stage involving several surrounding African nations, at other times as a simmering, but permanent conflict between rebel groups aka criminal gangs, who went on killing and raping and destroying whatever was left of the country; unhindered, no, even encouraged by the powers to be, who were scheming over the control of mineral riches.

The few times Congo reached the news other than during its occasional questionable elections, I read about a film crew kayaking the Congo River, when their guide is dragged into the water by a crocodile, and whose body has never been found again. Or about another Western traveller who canoed down the river, and got killed by the locals; very few details were available, except that he was never seen again. Hmm.

Enthusiasm for the trip waned, somewhat. Not that I ever contemplated canoeing down the river, I would just take public ferries. But these are not particularly safe, either. Other newspaper articles are about rusty old ships that sink, or improvised boats – from tying together a number of pirogues – that crash. These incidents often leave tens, if not hundreds of people dead and missing. It doesn’t help that some survivors of a boat fire in 2014 claim that local fishermen, instead of helping the people in the water, beat them with oars, and went on to loot from the burning vessel, instead. Hmmm.

the alternative: reading

So when Covid-19 hit the world in 2020, travelling across borders became a real challenge, and we were forced to postpone several of our plans, I decided to dive into the Congo literature, and immerse myself in the country and its river for a few months: second-best to travelling. (The list is not exhaustive, you’ll find it back here, with some of my observations.)

Start with its history, for which there is no better introduction than David van Reybrouck’s “Congo: the Epic History of a People”, written in 2010. I am not going to repeat the contents of the book here, save that Congo’s history is as fascinating as it is horrible – and it is quite horrible! A country having been raped by first King Leopold of Belgium personally, then by the Belgian state and, after independence, by a variety of local politicians and war lords. It is an incredible history, of opportunism by the Belgians and later by the western world, led by the Americans, during the Cold War. Of naivety, incompetence and mismanagement in the period leading up to its independence in 1960, as well as for decades afterwards, up to the day of today. Let’s just say that de term Democratic in the name of the country is, well, a misnomer.

the early traveller

But what I was really after, was travelogues from people who have been there. How is it to travel through this vast country, what can you expect? Wikipedia simply states that “Tourism in the Democratic Republic of the Congo is uncommon”. Right, I knew that much already. Yet, there have been travellers who have written about their experiences, not in the least the country’s most famous tourist ever, Henry Morton Stanley. Stanley’s second African journey, in 1875-1877 – after his first, to find David Livingstone in 1871 – was aimed at finding the source of the Nile, but instead identified the Congo River as a separate river system, which he subsequently followed all the way downstream, to the Atlantic Ocean, where he arrived after 999 days of expedition. Admittedly, he started in Zanzibar, at the eastern end of the African continent, but even if only one-third of his journey was taken up following the Congo River, this is still a lot more than I would be prepared spending on such a journey. In any case, times have changed, and obviously today’s travel is not comparable to Stanley’s.

what a trip would look like now

Or is it? My library also contains “Blood River”, written by journalist Tim Butcher in 2007. And guess what, Mr. Butcher was obsessed with the Congo River, and with recreating Stanley’s expedition. Which he did, sort of.

He flies into Kalemie, a decrepit town on the Congolese side of Lake Tanganyika, from where he sets out for a 500 km journey through the jungle to reach the river proper. There are no roads anymore, in Congo, only tracks. The only mode of transport is the motorbike. Mr Butcher spends 500 km riding pillion, passing groups of armed mai mai – local gangs -, with which his guide negotiates safe passage for a few packs of cigarettes, and a completely burnt-out village which has still the acrid smell of the fires. They arrive after dark in another village, where they overnight and leave again before daybreak. They reach a larger town halfway the second day, even more decrepit than Kalemie, only to fuel up and continue again, afraid that their presence may attract too much attention, and ultimately more armed gangs. Mr Butcher survives, barely, on sweets and energy bars, because there is no food along the way; he gets dehydrated because he doesn’t have enough clean water, and no time to boil extra water to fill his bottle. Well after dark on the second day, totally numb from pillion riding, he reaches Kasongo, on the river. He doesn’t write much about the things he saw along the way, except for an old iron bridge and some vague mention of the landscape. My guess is there wasn’t much to see, in the first place.

Does it get better, once he has reached the river? The town of Kasongo isn’t very exciting, to say the least. But at least he meets other people again, and he stays with an expatriate representative from an international NGO. After three days rebel issues elsewhere prompt the NGO to evacuate its expat staff, so Mr Butcher is put back on a motorbike again, to be driven to Kindu, where he can stay at one of the UN bases in the country. Here he finds out that there is no regular river traffic at all, anymore, and he struggles to find transport down river. A UN patrol boat takes him for a little while, and from where he is being dropped off, he immediately arranges a pirogue – not much more than a hollowed-out tree trunk – to take him further, realising that on the river he is safer than on land. Had I already mentioned that fear is the recurring theme, during Mr Butcher’s trip? After another few days, spent under the burning sun in a pirogue, he reaches Ubundu, a town at the upper end of the Stanley Falls, a series of cataracts. Here he finds a room with a Catholic priest, who tells him to leave as soon as he can, again, because it is not safe. Mai mai, rebels, armed gangs killing indiscriminately. So he gets back on the back of a bike again, this time from another international NGO, to be driven 150 km further downstream, past the cataracts – but without ever seeing the water, of course, the track that is left from what was ones a road, runs inland. To reach Kisangani, downstream of the Falls, the first large town on his trip, and a temporary heaven of security and stability, thanks to a large UN contingent.

Only 1734 km to go to Kinshasa. Before independence this would have been a piece of cake, with one of the regular ferries covering the distance in less than a week. The first option Mr Butcher finds may take four months, or perhaps doesn’t even get there. In any case, it hasn’t left yet when he has a lucky break, and manages to get onboard a UN-chartered boat, a good two weeks after his arrival in Kisangani. With which he sails 1000 km downstream in one go, to Mbandaka. He describes the view as ‘an endless forest, an unbroken screen of green’, for seven long days. Halfway the trip he falls ill, perhaps with malaria. In Mbandaka he tries to secure further transport, but like in Kisangani, there are no boat departures planned, securing passage downriver may take weeks. There is no hotel in Mbandaka. Mr Butcher, reluctantly, abandons the river and takes the next option, the weekly UN helicopter to Kinshasa. Helpfully, he notes that for most of the three hour trip all he could see was jungle.

Recovered, Mr Butcher does make the last part of the trip, from Kinshasa to Boma at the Atlantic Ocean, by car. Fait enough, as this part, full of cataracts, is unnavigable. The car trip is an equally difficult exercise, stringed together from the right contacts and bribes. And so he completes the Congo part of Stanley’s journey, that he had set out to emulate, and that in less than two months.

But all together, the disappointment oozes through his writing, first and foremost, I think, to do with what he has encountered. The decay, the destruction, and all the other hallmarks of a failed state. His rare excitement when he encounters an old metal bridge across one the Congo tributaries, fit for trucks, but with no road on either end anymore. Or when, during a forced stop because his motorbike breaks down, he accidentally stumbles on a cast iron railway sleeper and a piece of railway track, somewhere deep in the Congolese jungle. I suppose these encounters led to his most poignant observation, that unlike in the rest of the world, in much of the Congo the older people have had more exposure to modernity that the younger ones.

Don’t get me wrong: Mr Butcher’s is a fascinating book, rich with colonial and post-independence history. Rich with experiences of earlier adventurers, not only Stanley, and of a host of travellers from an earlier era. And rich with testimonies of people he encounters during his own trip, from very helpful local and expatriate NGO workers, from a Belgian priest and a British spinster who have spent their entire lives in the Congo, to ship’s captains and a host of intermediaries. But the journey itself? The constant fear? Hmmm.

So that was it. Dream shattered. No need anymore to go to the Democratic Republic of Congo, no need anymore to travel the river.

or reconsider?

Except that a few weeks after I had completed my Congo reading I came across an article in my local newspaper with photographs of the Kinact art festival, an annual happening in Kinshasa. Local artists make costumes out of rubbish found on the streets or the city’s dumps. They may prompt me to reconsider my above statement that I don’t need to go to the DRC anymore. But just Kinshasa, then, not the river.

(I even found a travel agency, called Kumakonda, that offers tailor-made trips to Congo, which means that there is a market, however small, after all. Check out https://kumakonda.com/destination/trips-to-congo-drc/)

Oh, and in the mean time I also found a book titled “Running the Amazon”. Who knows, after reading this I can tick off even more lingering travel plans.