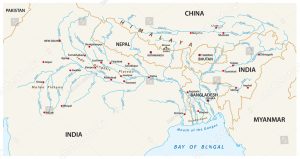

It wasn’t only the politics that challenged Bangladesh. Already before its independence, it was a poor country, and whatever was economically generated, was siphoned off by West Pakistan, at the time. The nine months Liberation War didn’t help, and besides, Bangladesh’s location at the mouth of several big rivers, like the 3000 km long Brahmaputra and the only mildly shorter Ganges, that together form an impressive delta in front of the Bay of Bengal, makes it prone to frequent floodings – the average elevation in most of the country is no more than 10 m!

there is an impressive anetwork of rivers ending up in the Bay of Bangal just in front of Bangladesh

Add to that the frequent occurrence of storms and cyclones which have a devastating effect on life and lives: in 1970 Cyclone Bhola killed an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 people, making it the deadliest tropical cyclone on record, in 1988 the country experienced one of the most devastating floods in its history with almost 60% of the country, including much of the capital Dhaka, submerged, a cyclone 1991 was responsible for the deaths of around 138,000 people, in 2007 Cyclone Sidr killed around 3,500 people and caused significant damage to property, infrastructure and agriculture, and as recently as 2019 Cyclone Fani displaced over a million people and once again wreaked havoc with crops and homes. But it was less deadly than previous cyclones. The good news is that the country gets more and more control over those disasters, with markedly less casualties each time again, and, I suppose, also less economic damage.

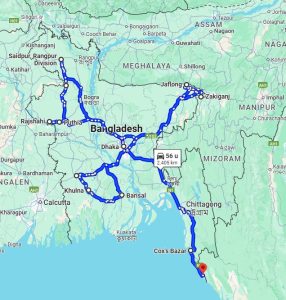

It is thus remarkable that the country has undergone such stable economic growth, of 5-6% per year. Despite the political upheaval, which normally comes with multiple strikes and demonstrations and is still marked by corruption, bureaucracy, weak institutions etc. We all know about the garment industry – and yes, also about the disaster with the Rana Plaza building that collapsed in 2013, killing 1134 people, mostly garment workers. The RMG industry, jargon for Ready-Made Garments, accounts for over 80% of Bangladesh’s export. But also leather, pharmaceuticals and shipbuilding contribute to the ever rising economy. In fact, shipbuilding started with shipbreaking, when following a 1960 cyclone a giant cargo ship ran aground near Chittagong and local metal workers slowly began to scrounge it for scrap metal. Nowadays, shipbreaking is big business, employing large numbers of cheap, semi- and unskilled labourers, and not hampered by safety rules and environmental considerations that play a role elsewhere.

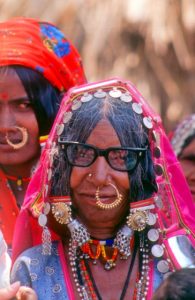

Although still on the UN’s list of Least Developed Copuntries, it expects to graduate from this list by 2026, which is testimony to its success in human development, poverty reduction and significant gains in term of economic robustness. It is still a poor country, but by far not as poor anymore as I would have thought initially. I know a lot more now than when I first thought about going to Bangladesh, for the rest we will go and see for ourselves (and add my own photos to this blog, instead of generic pictures from the internet). We may be in for a surprise, who knows?

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts