We finish our Czech journey in Terezin, a chilling relict from the Second World War, the prison and the Ghetto of what used to be known as Theresienstadt.

Perhaps we would have done better not to keep Theresienstadt – Terezin in Czech – for the end. A visit to this place, part concentration camp and Ghetto, part prison, is a thoroughly haunting experience. A depressing end to an otherwise uplifting journey.

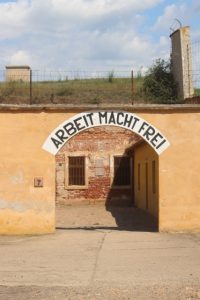

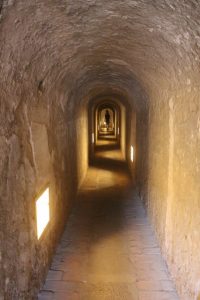

If fact Theresienstadt has two distinct elements. First, there is the so-called Small Fortress, the military barracks that were built in the 1780s, and, on and off, have been used as a prison. Gavrilo Princip, the assassin of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo 1914, was incarcerated here, and died here, too. After Czechoslovakia’s independence, post-WW I, local political prisoners were locked up in the Fortress. But the Small Fortress really gained notoriety when the German SS confiscated it in June 1940, and started to use it as a prison for people connected with the resistance. And for homosexuals. And for Jews, of course, who disobeyed the anti-Semitic laws – those who tried to escape the Ghetto, for instance. Obviously, there were far more prisoners than that the prison was built for. Sixty inmates to a cell were no exception, cells often with only one toilet, or without toilet at all, with chronic lack of water, no heating, but plenty of lice and other insects. Torture was the order of the day. In total, some 32,000 people were locked up in the Small Fortress; perhaps 8000 were deported “further east”, approximately 2500 didn’t survive the conditions in the camp itself, or were simply executed. Walking around here, passing under the Arbeit Macht Frei arch to one of the four courtyards, is a spine-chilling experience. Evil is tangible. And wandering around the complex in the company of many others, families with children – no doubt less than in normal times – is also unreal; these people don’t belong here, and neither do we, of course.

Yet, the other part of Theresienstadt, the less tangible part, is equally spine-chilling. This is the town itself, the town that was turned into a Jewish Ghetto and concentration camp at the stroke of a pen in October 1941, and would remain so until the end of the war. The Nazi command ordered the original inhabitants, perhaps 3500 of them, out, and started to move Jews from elsewhere in the country, and later also from other European countries, to Theresienstadt. Within a year the town’s population counted over 60,000 people, almost twenty times more than it was built for. Naturally, living conditions were appalling, men and women were separated and distributed over the already over-full dormitories in apartment buildings. A Jewish Council had been appointed to self-govern the Ghetto, assigning bunk beds to new arrivals, organising daily life and trying to uphold some form of normalcy, for instance by trying to maintain a kind of children’s education. The physical results are the many – once more, spine-chilling – drawings by children of their surroundings; seeing this through children’s eyes is just that little more painful. Incidentally, the Jewish Council was also tasked with identifying the people who had to be delivered to the train station, to fulfil the German-set quotas for deportation to the extermination camps, mostly the gas chambers of Auschwitz. From the 140,000 people that were sent to Theresienstadt, some 88,000 were deported. And although Theresienstadt was not an extermination camp itself, no less than 35,000 people perished, because of the living conditions, hunger, disease, leaving preciously few to be liberated by Russian troops in May 1945.

Let’s compare the numbers: roughly two/thirds of the prison population, which was mostly made up of resistance people, survived. Less than 15% of the Ghetto population, which were all Jews, survived. Yet, somehow the prison is the touristic attraction, tangible; you don’t see many people in the town, and not many in the two museums, either.

The Ghetto Museum, in the centre of town, shows a poignant film as well as a powerful exhibition on the history of the town during the war; here are also many of the children’s drawings displayed (similar to one of the synagogues in Josefov in Prague). The Magdeburg Barracks, former seat of the Jewish Council, is also open to the public. It shows a replica of the dormitories, which may well have been modelled on the many artist’s drawings that have been exhibited here, as well; testimony to the “sense of normalcy” that provided room for artistic expression in Ghetto times. But the most amazing thing is that all the other houses, apartment buildings that line the streets and that accommodated the thousands of Jews during the war, now seem to be occupied by the town’s inhabitants again. As if nothing has happened. Except that the atmosphere in town remains ‘unheimish’, spooky almost, if not exactly spine-chilling anymore.

next: the last entry, a look-back on the trip