Druskininkai is a small Lithuanian town in the far SE corner of the country, near the Belarus border. It is insignificant, except that it has somehow developed in the spa capital of Lithuania. “Druska” is Lithuanian for salt, and refers to salt springs that apparently form the basis for this development, although I have seen no hotels advertising a link to authentic spring water. Yet, each and every hotel seems to have a spa and sauna and massage and whatever else.

Druskininkai is also where the interests of my travel companion and of me diverted. Confronted with the opportunity to enjoy a last spa, before we are heading home again, she elected not to accompany me to the real reason for coming here, the Grutas Parkas, a few kilometers outside town.

sculpture Felix Dzerzhinsky, a bit of a Fidel Castro avant-la-lettre. He was a Polish revolutionary of aristocratic background, one of the founders of the Polish Lithuanian Social-democratic party in 1900. But he gained even more notoriety by establishing the Cheka, the first Bolshevik secret police, in 1917

sculpture Felix Zemaitis, a Lithuanian who became a major general in the Red Army, and was instrumental in the destruction of the Lithuanian army during the WWII

and this is how his sculpture stood in a public place, in the past, significantly elevated, so to speak

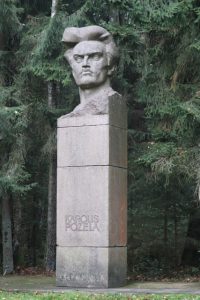

a sculpture of Karol Pozela, a local, leader of a communist anti-state underground organisation with a fabulous haircut, executed in 1926

and Karol was not alone at his execution, these other three guys also got the bullit in December 1926; Karol in the one on the left, recognisable at his hair-do

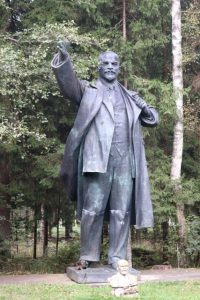

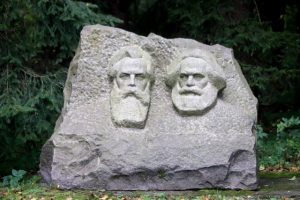

The Grutas Park ‘outdoor experience’ is – literally – a walk in the park, in this case a walk through a pine-forested park. A concrete path forms a loop through the forest and leads past a collection of statues and sculptures of prominent Soviet and communist Lithuanian characters, all bad guys (and one or two bad girls). In earlier days these decorated prominent public squares, but after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the reestablishment of Lithuanian independence, these people fell from their pedestal, sometimes literally. The museum has collected quite a few, and given them a new life. Lenin in over-represented, especially in the beginning of the park, Stalin only appears twice, and a few other Soviet terror-mongers also surface; the Lithuanian communists are less interesting for the outsider, but are compensated by a number of grand sculptures and decorative friezes, some damaged before the museum could salvage them. Some of the statues have fallen on the ground, and not been put back, perhaps because they are still so much hated? Or does the museum want to illustrate this aspect, too? Not everywhere is English explanation, sometimes there is no explanation at all, and sometimes there are numbers along the path, without exhibits, but all in all it is an entertaining walk, with enough information to get the message across: these were bad people.

The museum claims, on their website, that they are the only museum to exhibit Soviet relics, and that theirs’s is ‘a rare, and maybe even unique phenomenon in the world’. The ‘maybe’ suggests that they are probably well aware of that other museum, near Budapest, which also shows a collection of Soviet-era sculptures, and which I liked more, to be honest. Grutas Park is, after all, a bit dominant on individuals, not all of them that well known.

Next: on the way back, Gdansk.

this is a monument to the partisans. The Soviet Partisans in Lithuania spread from 1942 onwards, encouraged and organised by the Soviet Union and its Red Army. They were groups of saboteurs in the German-occupied country, consisting of a wide group of individuals, amongst them activists, Red Army men, escaped prisoners of war and Lithuanians, many of Jewish origin. They were not supported by the majority of local population, who had set up their own resistance groups. But the Soviets won, and the partisans survived in post-war roles as so-called ‘stribai’, provocateurs for the Russian secret service.