Leymebamba is another wonderful village in the Utcubamba Valley, with lovely people and a lugubrious museum, as well as further buriaal sites in the neighbourrhood.

Our next destination is Leymebamba, further down the valley of the Utcabamba River. Again, only an hour’s drive, if everything works. But our transport challenges aren’t over yet. We get down from Nuevo Tingo to the main road, only to find that no buses have passed yet, this morning. The buses need to come from Chachapoyas, but with more rain last night, the road has been flooded again, and none of the minibuses can get through. We have just installed ourselves in the morning sun in front of a road restaurant, mentally prepared for a long wait, when out of nowhere a minibus appears. Destination Leymebamba. How he got here? He took a two-hour detour from Chachapoyas, through the mountains, to avoid the floods. Great!

Except that we had, in the meantime, learned of further floods, on the other side of Nuevo Tingo. And indeed, ten minutes further a long line of cars was waiting, in front of another large water mass. But our hero driver had not made this detour to be stopped at the next flooding. Ignoring all the others, he steered his minibus into the lake, and miraculously, maybe 500 meters further, appeared on the other side again, with the engine still running and all passengers on board. On to Leymebamba.

The tiny little village of Leymebamba is know for two things. One, it has the friendliest population of any town or village in entire Peru (according to my 10-year old guide book), and two, it has an extraordinary museum. The people’s claim was easily confirmed. Life revolves around the small Plaza de Armas, where everybody seems to be hanging out. Greeting, wanting to know where we are from, and pointing us in the direction of the village phenomenon, water that in the rainy season comes from under the road, and flows through several streets. Which everybody is then again happy to discuss with us, in great detail. The lady from the tourist office almost forces us to come and see the church, of which she is very proud. In the local restaurant people make space in the evening, despite the fact that the television shows Peru playing football against El Salvador; the restaurant is packed. If it would have been for the people, we could have stayed much longer in Leymebamba.

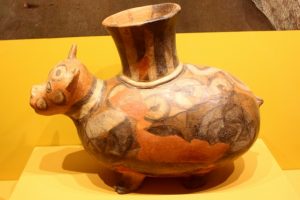

The museum is an hour’s walk outside town, and derives its fame from the 219 mummies that were found near a lake up in the mountains in 1997. Rather than take them to Lima, a purpose built research centre and museum was constructed outside Leymebamba, where studies on the mummies have been conducted since, and some of the mummies, together with artefacts found in the tombs, displayed. And the mummy room is indeed one of the most spectacular sights in the museum. The vast collection of mummies can be seen through a window – the room itself is, obviously, climate controlled. Many are still wound up in cloths, but from others the skeleton is visible, always in the same pose, kneeling and hands in front of the face, the way they were buried perhaps 500 year ago, at the end of the Chachapoyas era. What is remarkable is that these mummies have been preserved so well, in the wet and humid climate of the cloud forest; thought to be due to a combination of burial techniques and embalming, introduced into the Chachapoya culture by the Incas.

On our last day in Leymebamba we find a taxi driver who is prepared to take us to Revash, another burial place high up in the mountains, a bit like Karajai. This time, we climb – by car – to some 2800 m, to the village of San Bartolo, from where we take a walk – again, along a good path, the Peruvians know how to handle their cultural heritage – to Revash. This is the funerary site where burials took place by constructing miniature houses high up on ledges in the mountain side, in which the bodies were placed. The houses were painted, and left – except that grave robbers have done their work since, of course. Apart from the site itself, the trip up the mountain was already worth the effort, passing the tiniest villages, seeing how people here make a living. Barely, I would say. Yet they compete with Leymebamba for friendliest people of the country!

next: back across the Andes to Cajamarca