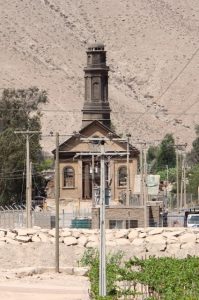

In order to cross the Andes, we move to Tierra Amarillia, a small village below the Pircas Negras Pass. On the way, mostly desert, mining and some surprising flora

As I said earlier, the plan is to move ever further north, in between the Pacific coast and the Andes. However, somewhere along we have picked up the idea to cross the Andes a few times, in a loop, once back into Argentina and then again into Chile. Crossing the Andes is fun: high mountain passes, surrounded by even higher peaks, spectacular landscape, you name it.

We rent a car in La Serena, and head north, for a clockwise loop, up the 4100 meter Pircas Negras Pass, apparently one of the most beautiful and remote crossings, and then down and south again to the Aquas Negra Pass, which climbs to well over 4700 meters. Will take a few days, and brings us back to the La Serena area, where we have a couple of other things on our itinerary.

Because the Pircas Negras crossing is a long one, we try to move up as far as possible on our first day, to Copiapo, from where the ascent eastwards starts. The further north we get, the dryer, the more desert-like the landscape. Bare mountain sides are increasingly covered with sand, blown up to the flanks of the mountains. Vegetation is almost entirely limited to cacti. Fascinating plants, and some of them support fruits and flowers, introducing a rare element of, albeit subtle, colour. Several parked train wagons suggest that the main industry here is mining. Oh, and energy farms with thousands and thousands of solar panels, which glister in the distance and look like giant lakes. This is what in Chile is known as Norte Chico, the small North, the beginning of the Atacama desert. And yes, we intend to go all the way, into the Norte Grande, and to the other end of the Atacama – but not just yet.

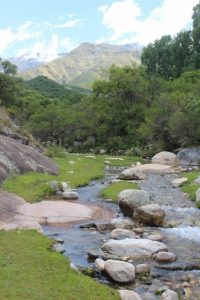

Actually, we established that Tierra Amarillia is the hotel-supporting village nearest to the pass – still a long way, almost 10 hours to the next hotel-supporting village, in Argentina. We take a shortcut, and find ourselves totally unexpectedly driving through an area full of grape vines and fruit trees, in stark contrast to the surrounding desert. The hotel is very basic, with container-like rooms serving the mining industry, but OK for the occasion. It even survives another earthquake, 5.9 this time, which wakes us up in the middle of the night.

This is also where the last fuel is available for a long way, so we fill the tank in the village, and buy an extra 20 liter jerry can: you better don’t run out of fuel on a trip through the middle of nowhere. Extra water, extra food, this is going to be an expedition!

And at the end of the afternoon we check with carabineros, the local police, to see if they have any suggestions, and to check on the road conditions. “Pircas Negras? No, the pass is closed. Already for more than a week, because of heavy rainfall and landslides”.

next: we do get to the border