One of the issues I have not yet discussed in great detail, is the head hunting history of the Naga, and especially of the Konyaks, who were apparently the fiercest, and who continued longest, probably well into the 1960s.

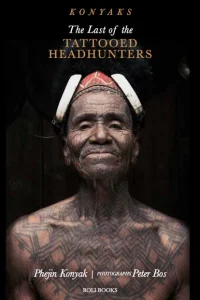

Our own guide is pretty useless, and not readily forthcoming with information, but we overhear the stories of some of the other guides, in our guesthouse, and in Longwa and Sheanghah Chingnyu. Although not everything we hear is always consistent, a book, ‘The Konyaks, the Last of the Tattooed Headhunters’ is very helpful (and also beautifully illustrated). ‘Taking a head’ was done in the believe that it brough prosperity and protection from evil spirits. But also to celebrate the inauguration of a new morung, or a log drum, or it was done by individuals to gain status in the community. It entitled them to special tattoos, mostly applied by specialist women tattoo artists, mostly the wife of the chief. Not only the faces were tattooed, also the rest of the body, especially chest and legs. One detail I find absolutely amazing is that victims were not necessarily always enemies that had done something that invoked revenge. Some of them were, but they could also be innocent passers-by. And head hunting raids were not necessarily heroic, often the individual who claimed the head was supported by a group of helpers, who overwhelmed the same innocent passer-by.

Our own guide is pretty useless, and not readily forthcoming with information, but we overhear the stories of some of the other guides, in our guesthouse, and in Longwa and Sheanghah Chingnyu. Although not everything we hear is always consistent, a book, ‘The Konyaks, the Last of the Tattooed Headhunters’ is very helpful (and also beautifully illustrated). ‘Taking a head’ was done in the believe that it brough prosperity and protection from evil spirits. But also to celebrate the inauguration of a new morung, or a log drum, or it was done by individuals to gain status in the community. It entitled them to special tattoos, mostly applied by specialist women tattoo artists, mostly the wife of the chief. Not only the faces were tattooed, also the rest of the body, especially chest and legs. One detail I find absolutely amazing is that victims were not necessarily always enemies that had done something that invoked revenge. Some of them were, but they could also be innocent passers-by. And head hunting raids were not necessarily heroic, often the individual who claimed the head was supported by a group of helpers, who overwhelmed the same innocent passer-by.

and this guy I originally classified as a fake – the white markings in the face are not tattoos – but I then noticed a similar chest and stomach tattoo, barely visible

Head hunting was officially banned by the British in 1935, but only for the so-called Administered Areas. The Konyak tribe lived in unadministered areas, and continued the practice until the 1970s – even though the Indian Government forbade it already in 1962 (and the church, active since the end of the 19th C, was also not a great admirer of the custom).

Fact is that there are less and less tattooed men, the ones who ‘took a head’. In Longwa sixteen, in Sheanghah Chingnyu only two. And not all of them are equally happy to be photographed, I sensed. Yet I managed to take pictures of several ancient warriors, even though sometimes under difficult circumstances, like the inside of a dark morung. Although a far cry from the photos in the book mentioned above, it is nevertheless a unique collection of something that will be entirely gone in another ten years, or so.

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts