The pre-colonial part of Lima is at least as impressive as its colonial part, with a well-preserved pyramid and some fabulous museums containing the nation’s treasures.

Of course, Lima is more than the old city centre; in fact it is a huge metropolis, with over ten million people on some 800 km, the third-largest in Latin America. And yet, even inside this metropolis the Peruvians have managed to unearth an ancient temple, the Huaca Pucllana, which served the so-called Lima culture between 200-700 AD, sort of time equivalent with the Moche in the north. But where the adobe pyramids of the Moche have been badly eroded by rain (or by deliberately diverting a river, like south of Trujillo), the Pucllana structure, also entirely adobe, is in a remarkable shape. Initially I was convinced that this had been reconstructed, but the guide – here too, entrance only with a guided tour – corrects me, firstly that ‘we don’t speak of reconstruction, but rather restoration’, and secondly, that most of the structure is actually in its original state. It never rains in Lima, that’s why.

All these huacas – temples or pyramids -, in Lima and everywhere else in the country, have yielded lots of treasures. Many of which have been lost through grave robbers – initially the Spanish, hunting for gold and silver, later Peruvians, feeding the black market for historical artefacts. But luckily quite a few have survived, and I have shown some of those earlier, as they were included in local on-site museums. Of course we expected that the best pieces would be in Lima, but nothing had prepared us for the two main museums here, the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History, and the private Larco Museum.

pottery from the Recuay culture, the same ones who did the stone sculptures in Huaraz (200 BC – 600 AD)

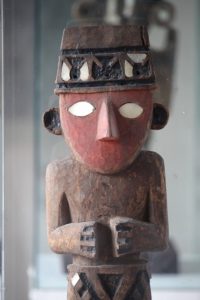

The National Museum takes a more chronological approach, the Larco Museum is more thematically organised. But both places obviously have had first choice in selecting what they wish to present. I don’t think I have ever spent so much time in a museum, perhaps with the exception of the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. Every piece is worth looking at, especially because what is on display – what is beautifully displayed, especially in the Larco Museum – is so different from what we are used to in the west. The most exquisite pottery, each culture having its unique characteristics, in shapes and in decoration. Fabulous gold and silver jewellery, or headdresses, or vessels. Thousands of years old textiles, intricate weavings with bird motifs. Even a few stone sculptures – not so many as in Huaraz, though -, and the occasional wooden piece, wood not being the favourite material in Peru. There is so much, and so much detail, that I am sure I could go back and spend another couple of hours there. Oh, and the Larco Museum also has an adjacent room, their depot, with cupboards full of more pottery, thousands of them, arranged by theme. It took me a while, but I did locate the decorative crabs. At a later stage I will devote individual entries to both museums – even more photographs!

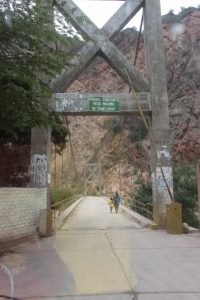

Outside huacas and museums Lima also has its fashionable neighbourhoods. Miraflores is one of them, mostly upmarket residential , with lots of trees and small parks, an attractive Malecon – coastal boulevard -, and some excellent restaurants; we have eaten very well, here! Another one is Barranco, further south, which is more romantic, older houses, some gingerbread-type, a nice square. The main attraction is the Puente de los Suspiros – the Bridge of Sighs -, in fact a rather underwhelming narrow thing, except that it is full of people on a Saturday afternoon. We make our way to the coast, which is not very far, and admire the sunset, that quintessential moment that we have admired all along the Pacific Coast, the past few months. With a Pisco Sour. Naturally.

next: wrap up with looking back