It takes a while to get there, but the Toro Muerto petroglyph site is worth all the effort: a unique art gallery in the middle of nowhere.

We return to the bus station in Tacna the next morning, to find that the strike has not been lifted yet. No busses. But there are collectivos, shared taxis, and if the road to Arequipa is closed, we can always go somewhere else, no? So we move, in steps, by shared taxi to Camana, further north along the coast. Not because of Camana, but because of an extensive collection of petroglyphs nearby, a site called Toro Muerto.

Well, nearby: the only way to get to the village of Corire, next to Toro Muerto, is by taking a couple of connecting mini-buses, a system that works surprisingly well for short distances, of say, an hour or so, unless your luck runs out and the connecting bus, which leaves when full – no time schedules here – leaves just before you arrive. Our luck ran out three times, today.

The drive to Corire yields another surprise: the valley we descent in is covered with rice paddies – and grapes, for good measure. The contrast between the dry, featureless desert and the beautifully green valley is striking, and to think that just one river can supply the water for growing extensive amounts of rice, in the desert! And grapes, which are, guess what, turned into wine and pisco.

In Corire we take a taxi to the site, where we arrive just before the ticket official arrives, on his motorbike. Somebody must have told them there are tourists in town, the news spreads fast. But we are glad he arrived. There are literally thousands of large boulders in this valley, of which hundreds have been carved with petroglyphs. The official points us in the right direction, where the best images are, and the most – which saves us from checking each and every boulder!

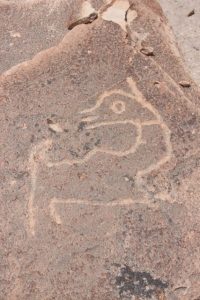

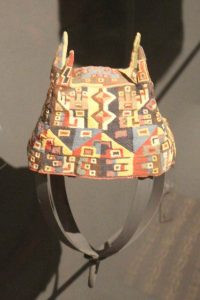

We spend the next one-and-a-half hours, or so, wandering in between rocks, admiring a wide variety of images, apparently carved between 200-1300 AD. There are lots of different animals, something cat-like, a puma perhaps, snakes, lots of lamas, and lots of animals very similar to the ones on the Piedra del Guanacos. Some vey basically scratched out of the rocks, others much more elaborately worked on. People dancing, some with extensive headdress, the shamans probably. And lots of geometric figures, zig-zag lines are a repeating theme, as well as widely-carved straight lines, and the occasional sun. To be sure, so once in a while, vandals have been adding to the images, but not much, not as disturbing as in Kirgizstan and Tajikistan, where we were a few years ago. Somebody has tried to chop off a piece – and may have succeeded, no trace of the other half. But mostly, this is just a mysterious collection of images, in a remote place, and a place we have for our own this morning. Which is part of the enjoyment, of course.

A fabulous art gallery, only to be seen here, nowhere else.

next: Nasca, of Nasca line fame