We arrived all right in Tehran, but were immediately arrested! Introduction to Iranian hospitality.

In order to get to Iran, most people will need a visa, so we headed for the Iranian Embassy in The Hague some time ago. Visa rules change continuously, of course, but all internet resources I had checked are adamant that 30 days is the absolute maximum – and extending the visa inside Iran can be a hassle. Without even asking for it – I only put our planned entry and exit day on the visa form -, we got 60 days. Good start! Next, we booked a ticket, and eh… read a few books and a travel guide, looked at some websites and fellow traveller blogs, which all together led to the Plan. And then we were ready to go, off to Tehran, off to two months of freedom, with a rough itinerary.

Well, not so quick! As soon as we landed in Tehran we were kidnapped, and held hostage in a safe-house for two full days. No kidding! Iranian friends of ours in The Netherlands, who we had told about our plans, were possibly even more excited than we were, and immediately mobilised family members to pick us up from the airport, and take us to their house. They, in turn, had mobilised more family members, who took us to a park next to an artificial lake, grandly called the Persian Gulf Lake. Great experience; this is what Tehranis do on Friday late afternoon and evening, when the temperature cools a little: they move en masse to the parks, armed with baskets full of food, with small barbecues, with badminton rackets and volleyballs, and a host of carpets; they then set up base under a tree, or in one of the many, no doubt purpose-built, pergolas, and spend the rest of the evening together. And lazily paddle around in a pedalo. And eat lots of icecream, or corn-on-the-cob, or drink fresh fruit juices.

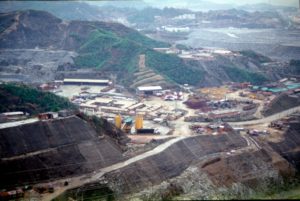

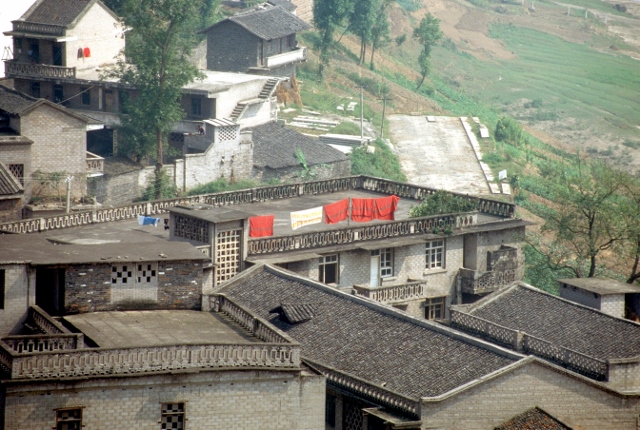

We did manage to escape the house for a while the next day, but only under guard. A stroll around revealed a modern, perhaps 15-20 year old, residential neighbourhood, with 4-5 story appartment blocks. Not the Soviet-style palatis I have described from the Balkans of Central Asia, no, these are fairly luxurous buildings, with some architectural inspiration, and spacious appartments. In between, there is room for the occasional park, which looks nice; green grass, flowers, trees, and lots of instruments to work out – which are enthusiastically being used, in the late afternoon when it is less hot. As are the children’s playgrounds, equily well equipped. All around Tehran there are more and more of these neighbourhoods, more or less luxurious, being built; a real construction boom.

That evening we negotiated our release for the following morning, but not after a last-minute invitation to dinner with yet more family members, in yet another safe-house; another wonderful evening, great food and a fantastic introduction to Iranian hospitality.

next: Tehran