Yesterday we got to Douala airport, checked in for our Air Senegal flight, and got to Cotonou, Benin’s commercial capital. All very civilised. Whizzed through custom, took an airconditioned taxi to our little hotel on the beach, and, eh, then we didn’t do much anymore, except consuming. This is quickly turning into a comfortable beach holiday!

We are a bit in a bind, because we need to join up with our truck-travelling group again, but we don’t know exactly how much time they will need to cross Nigeria. Worse, they don’t know either. So we have some days spare, to do some of the tourist bits in Benin that the group is unlikely to cover. In fact coming to Benin was one of the major drivers of our decision to join this trip, because ever since we lived in Haiti, with its distinct Voodoo culture, we have been interested in the roots thereof – which lie in Benin: this is where many of the Haitian slaves came from.

Ouidah

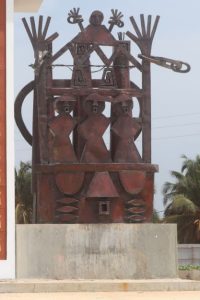

So where better to start then in Ouidah, the town where slaves were traded and put on transport to the New World. Back home I had consulted my 20 year old guidebook, which mentions the Musée d’Histoire de Ouidah, housed in the beautiful Fortaleza São João Batista, a Portuguese fort built in 1721. It retraces the town’s slave-trading history and explores the links between Benin, Brazil and the Caribbean. It also recommends the Route of the Slaves, a walk from the slave auction plaza, past the Tree of Forgetfulness (where slaves were branded with their owners’ symbols and, to make them forget where they came from, forced to walk around the tree in circles) and the Tree of Return, another tree the slaves often circled with the belief that their souls would return home after death, to a poignant memorial on the beach, Gate of No Return, with a bas-relief depicting slaves in chains.

Right! The museum is closed for redevelopment, so only the outside of the fort can be admired. Which has already been redeveloped, with little regard for any historical authenticity, walls have been plastered over, wooden balconies newly built. I am not allowed in, a guard stops me at the door – and then requests the astronomical amount of 100,000 West African Francs to let me peep inside. When I refuse, he walks away, giving me the opportunity to try the door, which is not locked, and peep inside. Glad I didn’t pay, it is really not worth it. I then ignore the angry guard, who comes running back but is way too late.

A small part of the museum’s collection is temporarily exhibited in the Casa Do Bresil, an equally crudely restored colonial building, where we are, of course, once again not allowed to take pictures inside. The museum guide then points our driver in the right direction for the Route of the Slaves – which is a relief, because hitherto we have been driving criss-cross through town, completely lost, whilst Abubakar, the driver, was insisting that he knew exactly where to go.

The slave market has already been redeveloped, into a square with a lot of copper-coloured balls. An old tree survives, but a local guide tells us that this is not the Tree of Forgetfulness, neither the Tree of Return, they both haven’t survived the redevelopment plan and were chopped down earlier. From here, a new road is being built to the beach, not yet finished, but drivable. Halfway is some compound, and a three-story building. Another local wants us to believe that inside this building the slaves were kept kneeling down: rather unlikely, as this is a four story concrete building clearly post-dating any slaving activities of the 19th Century, let alone earlier. But, there is the link with Haiti! A mural referring to Bois Kaiman, where the Haitian slave revolt initiated in the early 1800s.

one element we recognise, a mural referring to the slave revolt in Haiti, which started in Bois Kaiman

At the beach, more misery. Not so much of slave remembrance, but of construction: A Chinese company has been tasked with the redevelopment, and from the plans they display, it looks like this is going to be an enormous complex, with hundreds of parking places, artificial canals and ponds, boat trips, artisan markets. So far everything is fenced off. Equally at the other side, where the Gate of No Return is, officially invisible behind corrugated iron – with a little brute force I managed to create at least a view of the Gate. Nothing ‘poignant memorial’, it is horrible!

In short, there is nothing authentic, nothing original left here, and the memory of the slave trade from Ouidah is going to be commercially exploited through a themed fun park, theme Slavery. Question is, of course, who on earth is going to come all this way?

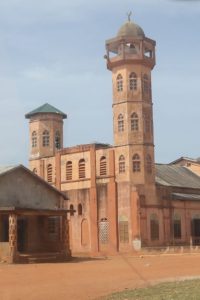

the front of the cathedral, obviously well maintained, perhaps by the same contractor who did the fort

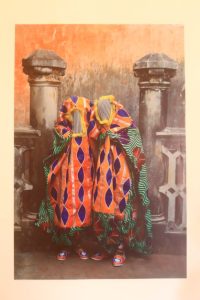

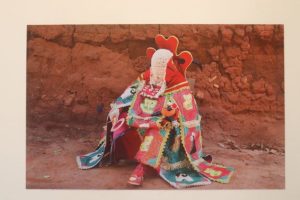

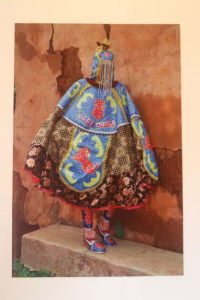

With the obligatory sights done, as far as possible, we have time on our hands. We wander around town a little, see some of what is left of the colonial architecture, including a mosque which could well have been a church earlier, and several old residences. We stumble upon the new basilica, a monstrous grey church which is, in its way, on seconds thought not even that ugly. Opposite is the Python temple, a Voodoo temple already mentioned in books describing the end of the 19th Century. And then we finally find something attractive in town: the Zinsou Foundation museum, focussed on modern, mostly African art. This is where the circle finally closes again: many of the Benin artists have used Voodoo symbols in their art works, and especially a series of photos is very impressive. At least we found the Voodoo back.

Next: Ganvie and Cotonou, in one entry

It’s a pity that most of the things you have seen was not authentic but the museum was lovely!