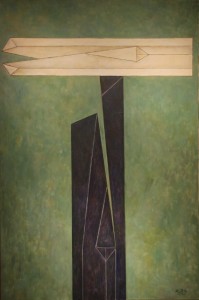

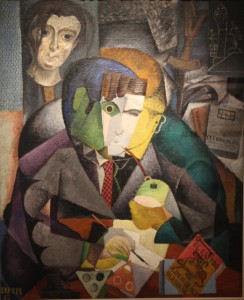

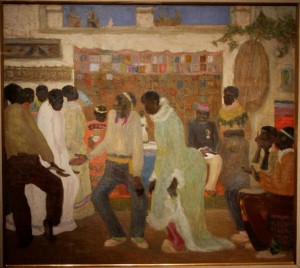

Excellent collection of modern art from Latin America

One of the newer museums in Buenos Aires is the MALBA (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires), established in 2001. The museum has a really nice collection of modern Latin American art works, a category that is often under-represented in museums across the world. A variety of paintings and sculptures from the 20th Century show that quite a few South Americans could compete quite well with their more famous colleagues in Europe. Mexicans Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo and Cuban Wilfredo Lam are perhaps the best known artists represented in the MALBA, but the works of a host of in Europe lesser-known Argentinean, Brazilian and Uruguayan artists are also well worth a visit to this museum.

A small sample of the collection, in pictures – nothing compared to the real thing, of course.

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts