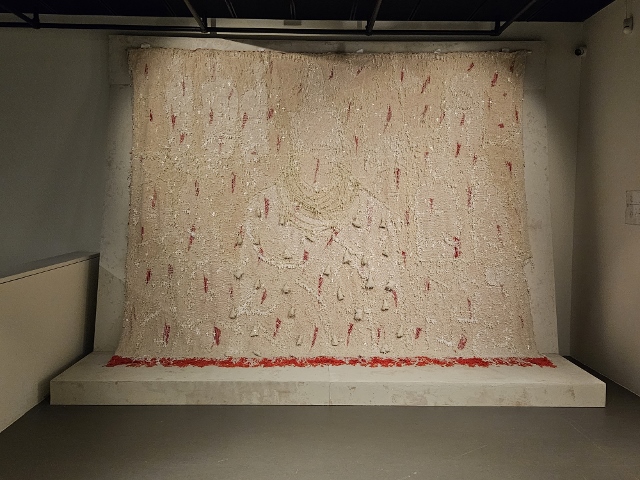

This work, presumably African because it hangs in the Afrika Museum, but without reference to artist or title, is actually not part of the exposition, but part of the permanent collection.

By the time you read this is, it is probably too late not only to go and see this exhibition, but also to go and see the Afrika Museum in Berg en Dal, near Nijmegen in The Netherlands. Through an unfortunate conflict between the owners of the museum and the organisation that exploits it, the museum will close by the end of November 2023.

The Afrika Museum is best known because of its unique collection of African masks and sculptures, collected by generations of missionary priests of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit, which brought back these pieces from their various posts in Africa. However, during recent years the museum has also collected a number of modern African art works, and together with works borrowed from other institutions, it has now put together a small exhibition, called ‘In Brilliant Light’. Fascinating art, a struggle between what is African, and what has been influenced by Western art norms. A pity it is so small, and a pity it mostly found works of Nigerian, South African and Cuban artists (‘African’ includes its diaspora), but very interesting and calling for more, nevertheless.

‘Awakening’ (1961, bronze) Perhaps for historical reasons – this sculpture was the first contemporary art purchase of the museum – a small replica of the Igbo earth goddess Ani is included, by Nigerian Ben Enwonwu (1917-1994). Much larger versions of this sculpture are inside the UN building in new York, and in front of the national Museum in Lagos.

‘L’offrande’ (1966-1974, oil on canvas) This painting Senegalese Bocar Pethe Diong (1946-1989) was donated to the museum by the Senegalese president Senghor, when he visited the museum, who strongly believed in Negritude, the art movement promoting the African way in the arts, free of the traditions of the colonial powers. Which, however, in fact seems to reinforce European stereotypes, as in this painting and the next – which is why this earliest African movement isn’t very popular anymore amongst present-day artists.

‘La femme qui crie’ (1961-1966, oil on canvas) This painting, from Senegalese Iba N’Diaye (1928-2008), is obviously inspired by Edvard Munch’s famous ‘The Cry’.

‘Sphinx II’ (1999, charcoal, pastels and watercolour on paper) This is an early work by Deborah Bell, one of the more famous contemporary artists from South Africa.

‘L’offrande des Couleurs’ (2013, textile) This work, a wall hanging by Abdoulaye Konate from Mali, is inspired on a hunter’s tunic – a body an arms widespread – which refers to divination and the use of oracles, an important element in the preparation for the hunt. The colours red, white and black are those of the offerings: cola nuts, milk and the ox.

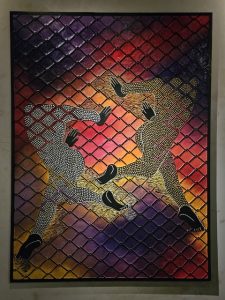

‘Niloro’ (1991, ink on paper) One of the most impressive works, this collagraphy (a printing technique) of female artist Belkis Ayon from Cuba is inspired by the Abakua, a Cuban secret society similar to those in many African communities. The Abakua is all-male, and based on secret rules that cannot be shared with outsiders, which is why most of the figures have no mouth. The white person on the floor is Princess Silkan, the only woman in the religion, who was killed – white is the colour of death – after she had broken the rule of silence. Ayon’s work is obviously an indictment of male-dominated society.

‘A Flutist with a Strange, Unseen Ghost’ (paint on triplex) and ‘Rainbow Goddess II’ (paint, linen, triplex)These two works by Olaniya Osuntoki, better known as Twins Seven Seven (Nigeria, 1944-2011) are deeply rooted in Yoruba imagery. Apparently, the artist, who was also a dancer, musician, poet, writer and sculptor, was the one surviving child of no less than seven twins his parents had. Especially the ‘flutist’ is so quintessential African, in my view, representing images, carvings, ancestor ceremonies and myths.

‘Pushing the Edge’ (2022, handcarved MDF panel, paint and varnish) and ‘Soulful’ (2022, id) Both works show headless, but colourful figures – the left one has in fact a whole range of small faces painted inside the body. They represent the artist’s ancestors, headless ‘because we may not know the identities of our ancestors’. The artist is Sthenjwa Luthuli, from Aouth Africa.

‘iSbonakaliso’ (2022, acrylic on canvas) This is South Africa artist Wonder Buhle Mbambo’s grandmother, covered in golden flowers, which refers to the native flowers used in ancestor ceremonies in Mbambo’s village. Also note the empty background, a range of dark hills under a pale blue sky, that higher up turns into a piece of cloth pinned in the canvas.

‘Transformation of the Devil’ (1997, wood, paint, glass and metal) And I love this one, by South African Masaego Johannes Segogela. Which shows the deep penetration of European beliefs in Africa. We see, in three steps, the devil (black, with horns, in the upper box), his transformation (being operated on by white angles, who have removed his horns, see the scars on his head, and are now working on the tail, middle box), and his reintegration (dressed in a suit, next to a priest, lower box). Whether this is the best example of art rooted in the African continent, is debatable, of course!

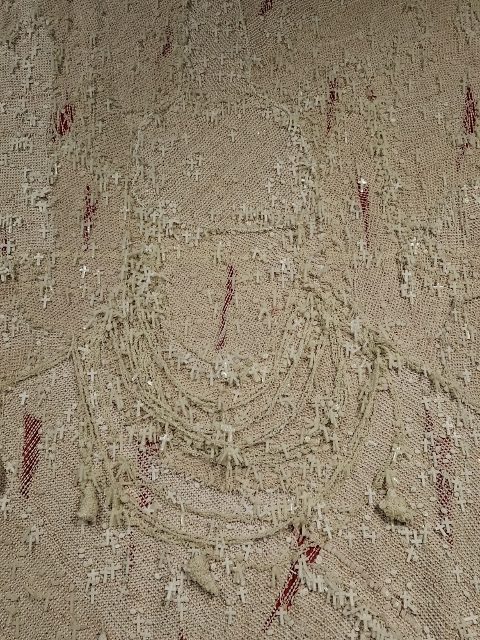

‘Ulin-Noifo, the lineage that never dies’ (2022, rosary beads, thread with stones, lace) Another wall hanging, this one from Nigerian artist Victor Ehikhamenor. The work combines symbols of Catholicism, like the rosaries, and those of the Kingdom of Benin: note the outline of a Nigerian king in the middle of the cloth.

‘Alagba in Limbo’ (1996, iron, feathers, mirror and wood) This impressive sculpture, from Nigerian Sokari Douglas Kemp, shows a group of who carry the body of a masked dancer, supposed to be the goddess Alagba, but in fact a man, a normal person. It illustrates the idea that the gods have abandoned the Nigerian delta, and have left the people with characters who play god. The link to the environmental damage in the Niger delta, caused by multinational oil companies, is obvious. The sculpture is actually not part of the exposition ‘In Brilliant Light’, but powerful enough not to be omitted from this entry. It is part of the permanent collection of the museum