In May and June of 2015 we finally traveled to Central Asia, the ex-Soviet Republics collectively referred to as the ‘Stans’. We started in the old Silk Road oases of Uzbekistan, then moved east through the Fergana Valley to Kyrgyzstan, and briefly into Kazachstan, before returning west via the Pamir Highway and the Wakhan Valley of Tajikistan. A journey with great variety, and many highlights, captured in lots of photos and stories – some general history, some personal experiences – of what is now called the ‘Stans’ blog.

In May and June of 2015 we finally traveled to Central Asia, the ex-Soviet Republics collectively referred to as the ‘Stans’. We started in the old Silk Road oases of Uzbekistan, then moved east through the Fergana Valley to Kyrgyzstan, and briefly into Kazachstan, before returning west via the Pamir Highway and the Wakhan Valley of Tajikistan. A journey with great variety, and many highlights, captured in lots of photos and stories – some general history, some personal experiences – of what is now called the ‘Stans’ blog.

01. the Stans plan: Our next journey will explore some of the relatively newly independent republics in Central Asia, as a continuation of our earlier Silk Road trip.

Years ago, whilst living in China, Sofia and I travelled the Silk Road, seven weeks from east to west China, from Xian to Kashgar, and then across the Karakoram Highway into Pakistan. Thoroughly exciting, thoroughly adventurous. However, the Silk Road was much more than that, a complex set of routes branching off in different directions, and one important part continued into Central Asia, across mountains with impressive names like the Pamirs and the Hindu Kush, and to exotic-sounding ancient places like Samarkand and Bukhara. We vowed to come back one day, to continue where we left it.

02. the Stans plan continued: Having adjusted our route several times, on account of visa and or time limitations, we have now a kind of a plan, through Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan

Not every country that ends on ‘stan’ is automatically considered one of the Stans. Afghanistan, Pakistan, they are entities in their own right, with their own specific problems. The Stans, that refers generally to the five ex-Soviet republics in Central Asia, Kazakhstan being the biggest, Uzbekistan the most populous, Turkmenistan the most dictatorial, Kirgizstan the most liberal and Tajikistan the poorest. Mind you, each of these five are also entities in their own right, with their own specific idiosyncrasies, their oddities and their challenges. But having been part of the Soviet Union also has created similarities, which somewhat justifies grouping them as the Stans.

03. the visas: You don’t just go to the Stans, no, you need major advance preparation to collect all the necessary visas and permits; but, we managed!

First the good news: for Dutch citizens, as for most citizens from OECD countries, Kirgizstan is since a couple of years visa-free. And, equally important if you are travelling overland, apparently the border guards know this, too. Another bit of good news: the Kazakh government is currently experimenting with visa-free travel for 10 countries, amongst which The Netherlands, a trial from 15 July 2014 to 15 July 2015: we’ll make that well in time should we opt for the Almaty excursion.

For the other two countries, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, we will need visas.

04. the arrival

The planning was perfect, as always: an afternoon flight from Amsterdam, change in Kiev (at this moment a safer bet, I think, that Athens, for instance), arrive early morning in Tashkent and connect less than three hours later to Nukus, our first destination. A bit of a tough night, but he, you can sleep on a plane, right?

Less than 24 hours before departure the Kiev-Tashkent flight was cancelled, and we were re-routed via Rome (still not Athens, at least), but with a very early morning departure from Amsterdam, and a connection on Uzbekistan Airlines. A trip down memory lane. I don’t know when they started building Boings 757, but the first one must be still flying for Uzbekistan Airways. Without ever having been refurbished. Remember the television screens that flap down from the ceiling? The very small ones, yes. Everything else was equally nineteen-seventies, the food, the pepsi cola, the stewardesses, the head phones, even the films (Yogi Bear!). And the leg space, folded double behind the seat in front of me. But he, you can sleep on a plane, right?

05. Nukus: Soviet-style town, capital of Karakalpakstan, Nukus has little to offer the visitor, except for a view of the river, a hyge cemetery, and especially, the museum.

Our first stop this journey is Nukus, the capital of our first ‘stan’, Karakalpakstan – technically not a real ‘stan’, because it was never an autonomous SSR (Socialist Soviet Republic), but only an autonomous region within Uzbekistan. According to our guidebook, Nukus “is of limited interest to either tourists or inhabitants”. Which is a little harsh. It is actually an example of how the Soviets went about designing a new town. Ella Maillart, a Swiss woman who travelled what was then called Turkestan in 1933, arrived at the village of Nukuss on her way back to Moskou, to be told that soon they would be building a new city here. They did.

06. the museum: There is not much in Nukus, the capital of Karakalpakstan, except for the State Museum of Arts. But what a museum it is, full of once-forbidden Russian avant-garde art.

Karakalpakstan isn’t the most exciting part of Uzbekistan, its capital city Nukus is – hopefully – also not the most exciting town. But it has one unique feature: the Nukus Museum, short for the “Karakalpak State Museum of Arts named after I.V.Savitsky”.

07. the Aral Sea

The story of the Aral Sea is pretty well known, I think. Once the world’s fourth largest inland water body, on the border between Kazachstan and Uzbekistan, this lake has been reduced to less than 10% of its original size thanks to the introduction of a cotton mono-culture. Cotton requires extensive irrigation, for which the water of the two main rivers in Central Asia, the Syr Darya and the Amu Darya, was used, robbing the Aral Sea of its inflow. The Fergana Valley in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan, uses most of the Syr Darya, and parts of Tajikistan and the areas around Smamarkand, Bhukara and Khiva drain the Amu Darya. All this causes an environmental disaster: excessive salination of the water reduced the fish stocks to a pittance, and the receding water line changed the climate, turning summers hotter and winters longer and colder.

08. the mud castles: The desert between Nukus and Khiva contains a range of ancient castles, impressive solitary hill top fortifications that are fun to climb and explore.

Outside Nukus we have already seen the remains of one of the ancient mud-brick forts in Karakalpakstan, but there are many more in the area, and in the Khorezm province nearer to Khiva. Assuming a certain similarity between these castles, we opted to go and see just a few, en route from Nukus to Khiva.

Why anybody would have wanted to build a castle, in the middle of the desert, was long unclear to me, until I read somewhere that originally, say 2-3000 years ago, the Amu Darya just vanished in the desert, in a large swampy delta, which created a fertile zone attracting lots of population – and population, of course, needs to be controlled by war lords, I suspect not different from the present day situation in Afghanistan or Somalia.

09. Khiva: Well-preserved, albeit not so very ancient walled city with many attractive buildings, and an interesting bazaar to escape the flow of visitors

Although Khiva may well have existed for a very long time, and may even have been an oasis at the time of trade along the Silk Road, present day Khiva really only came into existence in the 16th Century – at a time that the overland trade was already in decline. Which might as well, because Khiva was chiefly known for its cruelty. My travel guidebook puts it nicely: “Treachery and murder suffused daily life, and too often trade took a backseat to theft”. The most successful trade was the slave market.

10. Bukhara: Once Central Asia’s holiest place, laid-back Bukhara is a delight to wander around, through the backstreets or past the monuments, and has some unexpected surprises, too

There are several means of traveling from Khiva to Bukhara. There are trains, leaving from Urgenj, a bigger town half-an-hour’s drive away. Or busses, also leaving from Urgenj, and taking nine hours. Or one can take a shared taxi, which is what we opted for. Comfortable, and with six hours only a lot quicker than train or bus. Given the now-familiar desert-like countryside, the shorter travel the better.

Bukhara, like Khiva, was another of the relatively small Middle Age khanates that had established themselves in this part of Central Asia, and were forever at loggerheads with their neighbours. But Bukhara, unlike Khiva, was also an important city much earlier.

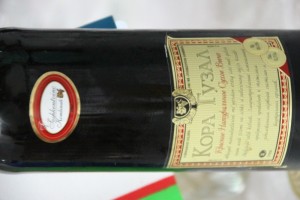

11. the wine tasting: What I didn’t know, Uzbekistan actually produces several wines, some of which we tasted.

The one thing that keeps surprising me is the near-universal production of wine. Almost every country seems to make some of it, seemingly regardless of climate, or religion. My first confrontation – which it was – was with Dodoma Red in Tanzania, of all places, and since then I have had locally produced wine in such unlikely places as India, Ethiopia and even Cambodia.

So I should have expected Uzbekistan, despite being a Muslim country, to produce its own wine, why not? Already on our first day, in Nukus, we discovered some home-grown wine (which we bought, and a week later poured through the sink shortly after opening). Yet, in a Khivan restaurant we were pleasantly surprised by a local dry red wine, which was quite drinkable.

12. Samarkand: Long-time Silk Road oasis refurbished by Uzbekistan’s national hero, Tamerlane, has some fabulous architecture, but lacks the magic

We took the train, from Bukhara to Samarkand, very comfortable, three hours, piece of cake, really. One departs from a vokzal, the same in the entire former Soviet Union, the word derived from Vauxhall, which was the London station visited by two Russian engineers in the 19th Century, who took the name for a generic, and so introduced it in the Russian language. Taxi into town, the price negotiated down to, according to the driver, “the price of a cup of coffee” (hard to believe that anybody in this country would pay $5 for a coffee), and, with some difficulty, found ourselves accommodation in one of the old courtyard houses – the few of them that have not been bulldozed down. Easy walking distance from the monuments that make this town so famous.

13. Shakhrisabz: Tamerlane’s birthplace is not yet entirely ready to receive the tourists, but the raw ingredients are there

Tamerlane wasn’t born in Samarkand, but some 90 km further south in the town of Kesh, which he turned into the city of Shakhrisabz, named after the many green gardens that he commissioned. He built a gigantic palace, the Ak Serai (White Palace), of which only a small part still stands upright, and he – and his grandson, Uleg Beg – built mausoleums for the family, and mosques and madrasses. A visit to Shakhrisabz is a standard day trip from Samarkand, so we complied, and we rented a car and driver, together with a couple of Russian fellow travellers.

14. Tashkent: The Uzbek capital is mostly big and ugly, although the old town and the Chorsu Bazaar add some couleur local

I recently learnt that Tashkent had been the fourth largest city in the former Soviet Union (after Moscow, St. Petersburg and Kiev). Today I actually realised what that means. Tashkent is huge, with wide avenues and enormous parks, once again lots of green. Walking it takes some stamina! Yet that is precisely what we did on our first afternoon.

Incidentally, there is no need to walk in Tashkent. Quite a few official taxis cruise the streets, and every other saloon car seems to serve as a taxi, too. You can just about hail every car, and pay seldom more than 1-2 US$ for a trip in the city. Not much future for Uber here. There are busses, trams, trolley busses, and then there is the metro, four intersecting lines, every five minutes a train. But to appreciate Tashkent’s size, you have to walk at least part of the city.

15. the opportunist: A bit if general history on Turkestan and Tashkent, and the remarkable, if short-lived, coup d’etat of one K.P.Osipov

As I have mentioned earlier, much of Turkestan, the name by which Central Asia was known before the Soviets introduced the current names of the Republics, had already been subjugated to Russian, Tsarist rule in the 19th Century. This was the time the Russians expanded east and southeast, with the ultimate objective to threaten the British Empire in India – a kind of an early Cold War dubbed the Great Game. This had been concluded with a treaty at the end of that same century, the treaty that created the strange North-eastern pan handle of Afghanistan as the buffer zone between the then-British and then-Russian Empires. Subsequently, Britain and Russia found themselves at the same side in the 1st World War, until the Russians suddenly withdrew from the battle against the Central Powers, mainly Germany, Austro-Hungary and Turkey, because of the Bolshevik revolution at home in 1917. Russia was suddenly fighting a civil war, where the so-called White Russians, loyal to the Tsar, were battling the Red Army of the Bolsheviks, and this extended into Turkestan, of which Tashkent was the Bolsheviks bulwark.

16. the Fergana Valley: The eastern-most part of Uzbekistan, the Fergana Valley, is not particularly pretty, but the friendliness of the Uzbek people easily makes up for that

And now for the hard part; the easy weeks of our trip are already behind us. In touristic western Uzbekistan people speak enough English to help us out, if we don’t understand the locals, and quite a few things are written in Roman script. But already in Tashkent we experienced several challenges, menus in Cyrillic only, without pictures of the dishes, and quite a few times a complete lack of English, or any other Western European languages. Russian, yes, but unfortunately, our Russian, even Sofia’s, is almost non-existent. The further east we go, the more Cyrillic-only things become.

The eastern part of Uzbekistan, east of Tashkent, is called the Fergana Valley, a huge, fertile stretch of land that extends into Kyrgyzstan.

17. Margilan: The silk capital of the Fergana Valley, Margilan is a friendly, colourful town where one can easily spend hours in the various bazaars

Margilan, close to Fergana, is a much older town, a trading stop on the Silk Road and a centre of silk production in its own right already in the 9the Century. Silk remained a dominant product throughout the Soviet years, when hundreds of thousands of parachutes were produced here, in addition to lots of other silks, and even now, according to one of our local sources, some 70% of the 200,000 population is involved in one way or another in the silk industry, mostly by weaving at home.

18. Osh: Kyrgyzstan’s second city, Osh, is in fact a rather small-town affair, but marked by both ancient myth and more recent history

Our time is up, in Uzbekistan. We head for the border with Kyrgyzstan, once again a couple of shared taxis away. In fact, we buy all the seats in the taxi, which provides ample space for our luggage and ourselves. Land border crossings are notorious, in this part of the world (and in many others), with customs officers trying to shake down unsuspecting tourists, soliciting bribes whilst searching your luggage, or just being difficult because they can. Especially exiting Uzbekistan, with its strict rules on registration and on foreign currency, is supposed to be bad.

None of it. A friendly customs officer called his friend as soon as he realised our origins, to discuss in detail the Dutch football competition, and the merits of Messi and Maradona, and that took most of the time, really.

19. Bishkek: Pleasant but slowly dilapidating small-town capital of Kyrgyzstan holds a unexpected, and un-apologetic, shrine to Lenin in its museum

In Osh we encountered our first set-back. We had planned to cross Kyrgyzstan from west to east, slowly, traveling from place to place, enjoying the landscape and a more rural setting, but apparently, the road, the only one, is closed – or broken, or impassable, we never learned what the exact problem was (that old language barrier again, you know). So we took a plane, and flew to Bishkek, the Kyrgyz capital.

I suppose first impressions count for much when you get to a new place, and with rain pouring down the evening we arrived, as well as the next day, our first impression wasn’t great. As in many other cities we have been to so far this trip, Bishkek is also falling apart: some of the roads on the way in have enormous potholes, the many parks could do with some maintenance, cutting the grass for starters, and pavements need urgent repairs – especially obvious when it rains heavily!

20. the balbals: In several places in Kyrgyzstan one finds balbals, ancient burial markers, but the collection at the Burana Tower is the largest

Bishkek doesn’t have much in terms of monuments, which is why they make much of the Burana Tower, located near the town of Tokmak about an hour outside Bishkek and the only remaining structure of Balasagum, a 10th Century city that has over the years been reduced to rubble thanks to a succession of earthquakes. The Tower itself is not that impressive, although the view from the top, over the snowy peaks in the distance and the cattle herds nearby, is pleasant enough.

What attracted us most were the balbals, Turkic-origin burial stones dating from the 6th-10th Century.

21. Almaty: The most cosmopolitan city in Central Asia, Almaty is booming, rapidly shedding its Soviet past, although the Soviet-era Victory Day is still being celebrated, in ballet-form!

It is hard to believe we are still in Central Asia! After three weeks of travel through mostly dilapidating cities, admittedly with some great monuments and some colourful bazaars, but with most of its Soviet era infrastructure and architecture showing distinct signs of age, we have arrived in Almaty, a modern city with trendy cafes and restaurants, well-equipped outside terraces, fashion shops and levelled pavements. Even the Soviet architecture looks more attractive than elsewhere, the outskirts are full of new, colourful apartment buildings, and even the palatis in town – the ubiquitous Soviet-style housing blocks – seem better maintained than we have seen in most other places.

22. Cholpon-Ata: Out-of-season lake resort with somewhat underwhelming ancient petroglyphs

The prime tourist attraction in Kyrgyzstan is the Issyk-Kol Lake, a large, slightly saline body of water in the Tien Shan Mountains. Issyk-Kol means warm lake, on account of a water temperature – at some 1600 m altitude, the lake nevertheless never freezes over- although ‘warm’ is perhaps not the first impression that comes to me, feeling the water. And the main resort town on the lake is Cholpon-Ata.

23. Karakol: Unpretentious, yet wonderful Kyrgyz town with charming architecture, and a famous animal market

Diving into Karakol one crosses some spectacularly sombre Soviet-style suburbs. You know, the now familiar apartment blocks, the palatis I have described before, but here completely lacking any form of decoration, any attempt to make them look attractive at all. And for the most part, slowly falling apart.

Yet, the inner town, if I may call it that way, is far more charming, with lots of small, originally Russian cottages – according to the local people we talk to, some close to 150 years old. Which is quite possible, as Karakol was built by Russian colonialists as a garrison town halfway the 19th Century, strategically positioned near the Chinese border.

24. Nicolai Przhevalsky: Near Karakol, we found a museum for the 19th Century Russian explorer Nicolai Przhevalsky

Those who have followed my other travelogues, or have inspected the various reading lists on this site, know about my fascination with early travellers and explorers, especially those of the 19th Century – ‘men of means and leisure’, quoting one of them. That fascination is, of course, largely limited to the English language domain.

So I never read any of the books Nicolai Przhevalsky wrote about his explorations, but I knew of Nicolai Przhevalsky. A Russian army officer, who was fascinated by unknown territory, and managed to convince the Russian Geographical Society to sponsor his travels – and the Russian army to grant him leave of absence, in exchange for all manner of strategic information Przhevalsky could gather on his travels. Which, coincidentally, concentrated on the ill-defined border areas between Imperial Russia and China, and those towards British India. Great Game, all over again.

25. the hot springs: Taking a walk in the park, and enjoying not only the view of the mountains, but also a hot spring

One of the things to do around Karakol is walking in the mountains that surround the lake; Karakol is sort of the unofficial Kyrgyz capital of hiking and trekking, from just walking up one of the many beautiful valleys in the vicinity, to six-seven day treks to far-away glaciers, or into Kazakhstan.

Luckily, for us, it is once again not yet the season – although even in season I don’t see us do multi-day treks carrying tent and equipment. But a good couple of hours walk in the mountains, that would be quite nice, of course, and the promise of a hot spring at the end, even better.

26. back to Bishkek: The way to travel in Kyrgyzstan is by minibus, quick and comfortable, which is what we did to get back to Bishkek

In order to start our third leg of the journey, traversing the Pamir Highway, we had to return to Bishkek, from where we had arranged a car and a driver. Although we usually prefer public transport, traveling the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan by bus may be a little more complex, mostly due to the lack of buses, or trucks that take the occasional passengers, and those that go, go irregularly.

Having said so, in the rest of Central Asia travel by public transport is extremely easy. I have already mentioned the shared taxis, that depart when full – or as soon as somebody agrees to buy the rest of the empty seats, and then it becomes a private taxi, all still very competitively priced. Our favourite, however, is the marshrutka, an 18-seater minibus that you see everywhere, here.

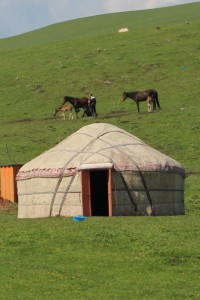

27. back to Osh: Our first cross-country trip over the mountains, and what a trip it was, with lots of snow-capped peaks, lots of animals on the move, and lots of yurts and lakes.

The Pamir Highway proper starts in Osh, the same town we had been arriving from Uzbekistan some two weeks earlier. To get there, with car and driver, takes two days, through some of the most spectacular countryside we have seen so far on this trip – although I suppose the term ‘spectacular’ perhaps alternated with ‘awesome’, ‘beautiful’, or just ‘woh’, linked to countryside, may occur more often in the weeks to come!

28. Uzgun: Uzgun sports a minaret and some old mausoleums, and a very friendly atmosphere, and is well worth the trip from Osh

Having already seen most of Osh, we had a day spare, which we used to drive to nearby Uzgun, a town with a series of three 10th-11th Century mausoleums. Of interest because of the intricate brickwork that was used in those days as decoration, well before the blue-coloured tiles became the norm. Perhaps because of the mausoleums, Uzgun receives quite a lot of pilgrims, and is a notably more religious town than we have seen so far, with a large number of mosques, and many women covered.

29. to Karakul: Our first stretch on the Pamir Highway takes us from green yurt-strewn valleys in Kyrgyzstan over high, desolate and windswept mountain passes, to the turqoise Karakul Lake in Tajikistan

The Pamir Highway, connecting Osh in Kyrgyzstan with Khorog, and ultimately Dushanbe, in Tajikistan, was built in the 1930s by the Soviet military, across some of the highest country on earth: the Pamirs are often referred to as ‘The Roof of the World’ (although that same epitaph has been assigned to Tibet, too), and the road crosses a number of significant high altitude passes.

Any ideas about the western concept of a highway need to be buried right here and now: the Pamir Highway is high, but has nothing to do with four lane motorways as we know them. Two lanes is the maximum, and often the road is quite a lot narrower than that; large parts are gravel-only, haven’t been sealed, and where there is tarmac, it is often badly potholed, or torn up by trucks. Not a comfortable ride. But all of that (and a lot more), we take for granted, because there are not many travel experiences more spectacular than driving the Pamir Highway.

30. Karakul: The reality of life in an idyllic-looking lake side village in the High Pamirs

Approaching Karakul in the late afternoon, the village of Karakul lies idyllic at the shore of the lake with the same name. At least, that is what it looks like from the car. As soon as we get out, to check in at the homestay, the wind catches us; even without it, it would have been freezing cold, but the strong blaze escalates the winter feeling, and accelerates the speed with which we add further clothing to our body. Mind you, it is the last day of May, but at 3900 m altitude, it never gets pleasantly warm here, even in August at midday the temperature doesn’t rise much above 15o C.

31. the homestay: Accomodation in the Pamir Mountains is in people’s homes, which comes witha few challenges for the comfort-loving Western traveler, but also with a bonus

We always knew that accommodation in the Pamirs was going to be limited, after all, there is not yet much of a mass tourist industry developed here. Especially in the smaller villages, and most are, hotels and guesthouses don’t exist, and the only option is Homestay, which means as much as staying with a local family, in their house, and eat what they eat. In much of the world this is touted as an excellent way to get acquainted with the local culture, but I have shared my own views on this on an earlier occasion: nice to see how they live, but due to the inevitable language barrier, there is not much in terms of communication, and thus not much in terms of mutual understanding. Highly overrated.

32. the geoglyphs: In search of ancient geoglyphs in the High Pamirs, we also encounter the elusive Marco Polo sheep, and a meteorite crater in between the high plateau river valleys and snow-capped mountains

A short distance from Karakul Soviet archeologists have found a number of strange rock patterns on a valley floor, and called them geoglyphs. Never heard of, so we had to go and see this.

‘A short distance’ in the Pamirs is not necessarily the same as ‘nearby’. Just after Karakul, we turned off the Pamir Highway, onto a dirt track across a gravel valley. And we kept on driving on a dirt track, or sometimes no discernible track at all, for the next two-and-a-half hours. Once again, incredible landscape, a desert at 4000 m…

33. to Murghab: Part Pamir Highway, part back road, we travel from Karakol across the highest pass, and via the small village of Rangkul, to Murghab

The distance from Karakul to Murghab isn’t that much, but with the trip to the geoglyphs of Shurali it took us two days, with an overnight stop in Rangkul, another small village, by far not as idyllic as Karakul, but equally cold and windy.

On the way to Rangkul we crossed the Akbaital Pass, with 4655 m the highest point of the Pamir Highway. Covered in jumpers and a fleece, I climbed even a little higher, for the view and a better photo vantage point, and wasn’t only frozen, back at the car, but also exhausted. But the views were worth it!

34. Murghab: The capital of the Eastern Pamirs is a small village, notable for its cemetery and its container bazaar only, and for its scenery outside town

In order to travel in the Pamirs, one needs a special permit for the Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomic Oblast (GBAO), which is what the Pamir region administratively is called. In Soviet times there were still some restrictions and special benefits for the people, but they have been abolished since independence, so what this autonomy means is a little unclear; it may well be a gesture towards the people of the Pamirs, who in 1992, during the Tajik civil war that followed independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union, briefly declared their own independent republic. It didn’t come that far, and these days the area is administratively, and also geologically, divided between a Western part, which is characterised by high peaks and deep valleys, and Eastern part, consisting of the high plateau mountains we have experienced the last few days. There are more differences between the West and East Pamirs, and one is that the population in the East is mostly of Kyrgyz ethnic origin, and is mostly involved in pastoralism: herding sheep and yaks.

Murghab is the centre of the Eastern part…

35. to Alichur: Continuing down the Pamir Highway from Murghab to Alichur, we encounter plenty of distractions, from rock paintings to adventures at the highest passes

Past Murghab, the Pamir Highway continues west, mostly across a 4000 m+ plateau, a wide expanse of gravel in which we occasionally recognise the Alichur river. There is a pass to cross, the Naizatash Pass at 4137 m, but you hardly notice this, the road climbs gradually, no hairpins or anything like that, and then descends again, equally gradually. All the time we are flanked by higher mountains, of course, which provide a dramatic backdrop to this section of road.

36. to Langar: Entering the Wakhan Valley, Afghanistan is only a stone’s throw away, and just as I imagined it to be

The Pamir Highway continues from Alichur west to Khorog, the main town at the other end of the Pamirs, but we had opted for a more round-about way, via the Wakhan Valley. This is where the Russians and the British, at the end of the Great Game, by treaty in 1895, created the Wakhan Corridor, a completely artificial, narrow strip of land to separate their respective empires (near Langar, our target for today, the corridor is only some 20 km wide). The corridor itself was to be part of Afghanistan, and still is. Never mind that there are ethnic Tajiks, and ethnic Kyrgyz, living on both sides of the rivers that form the border.

37. to Ishkashim: There are lots of ancient sites worth stopping for along the Panj River, the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan

At the village of Langar the Pamir River, that formed the border with Afghanistan, empties into to much larger Panj River – which now becomes the border. The Panj ultimately turns into the Amu Darya which we have seen earlier in Uzbekistan, the Oxus of antiquity. Langar is quite different from what we have experienced so far; instead of the dry and bare, wind-swept plateau villages with their dusty streets in between small, mud-brick houses, here the streets are lined with trees, the houses surrounded by agricultural patches of land with all kinds of crops. The word ‘lush’ is perhaps too generous, but everything is relative, and it is quite a relief to see so much green again.

38. the Afghan market: Another market, and once again a special one; just have a look at the portraits!

By now you are familiar with our enthusiasm for markets, and we were not going to miss the opportunity to roam around the weekly Saturday market outside Ishkashim, on an island in the Panj River, where Afghans and Tajiks come together to exchange their ware. The island is actually Afghan territory, and to get there we need to leave our passports with Tajik border police; the Afghan border control, which we never cross, is on the other side of the island.

39. Khorog: Exploring Khorog’s attractions, further down the Whakan Valley, and adventure travel to the high ranges of the Shakdara Valley

Further down the Panj River is Khorog, about two hours drive from Ishkashim. The scenery is much the same, quite densely populated on the Tajik side with agricultural villages following each other one by one, whilst the Afghan side seems a lot less developed.

Khorog itself is a pleasant small town, with even some traffic lights that serve a purpose, except that they are universally being ignored by the drivers, despite the omnipresence of police in the streets. Monday morning, there is even a bit of a traffic jam, around the market.

40. to Dushanbe: In two days we drive from Khorog to Dushanbe, the last part of the Pamir Highway, and inevitably somewhat less exciting

We continue to follow Panj down-river, still the border with Afghanistan. Where upstream the Afghan side had looked abandoned except for the occasional hamlet on an alluvial fan, it now looks busier and busier, with more and larger villages. An interesting observation is that houses on the Afghan side are compact, grouped together, whilst Tajik villages are set up much wider, individual houses with gardens in between. One wonders how much contact there really is, across the river, now mostly a forbidding fast-flowing stream in between steep mountain sides.

The road follows the river through the same narrow gorges, which occasionally widen to allow for the creation of small lakes and pools, where cattle drink and children swim.

41. Dushanbe: Tajikistan’s attractive capital is booming and well looked-after, unlike so many other Central Asian cities, with a pleasant tree-shaded centre and lots of construction in its outskirts

Dushanbe is not at all what we had expected. Over the past six weeks we have seen so many decaying towns, but not so Dushanbe. The outskirts, on almost all sides, is one big construction site, new buildings go up everywhere, and highrise, too. Ministries, apartment blocks – rapidly replacing the old Soviet-style palatis -, and many other, rather poorly defined, structures are being build, not necessarily very attractive, but clearly with more attempt towards design than in the old days; dark glass, somewhat frivolous balconies, and there is even some neo-neo classic – the application of half-pillars, stuck against the outside of the highrises. Tacky, perhaps, but they‘ll get away with it.

42. the tunnel: The Anzob tunnel, on the road between Tajikistan’s two main cities, is a nightmare; I show some video footage of the experience

In the old days the main road between Dushanbe and Tajikistan’s second city, Khujand, went across a high mountain pass, painstakingly zigzagging up, and down on the other side. No more! An Iranian company was given the task to drill a tunnel through the mountains, and they completed this, the Anzob Tunnel, in 2007, less than 10 years ago. Well, ‘completed’ is too much said. There is a hole on both sides of the mountains, and they are connected, but the road through the mountains has not been surfaced, the tunnel is leaking, there is water all over the place, and potholes are growing by the day. Our Landcruiser just about manages to get through, how smaller saloon cars do it, I don’t know. Some don’t, actually.

43. Penjikent: The area around Penjikent is home to two ancient cities, and, from the looks of it, an even older winery

In the western-most corner of Tajikistan is Penjikent, almost at the border with Uzbekistan, and tentalisingly close to Samarkand and its many tourists, if only the border between the two countries would be open – which it hasn’t been for several years now. Which is a pity, because Penjikent is home to two of the oldest settlement remains in Central Asia.

44. Istaravshan: Back in the lowlands, Istaravshan is a pleasant town, with mosques and markets, and with our own palati experience

Across yet another mountain ridge – or rather, through yet another mountain ridge, as we pass through the Sharistan Tunnel, a Chinese-built piece of engineering that contrasts sharply with the Anzob Tunnel -, we get once more into a different country. No more high mountains, except in the far distance, here we enter lowly lands again, agriculture and pastoralism exercised seemingly in harmony.

The main town is Istaravshan, also referred to as a poor man’s Bukhara. But it isn’t, really, Istaravshan is a city on its own merits, and just because it has an old town doesn’t call for any comparison.

45. the way back: The end of the journey, to Tashkent and back to Europe across the Kyzyl Kum desert

As our flight back home departed from Tashkent, we made our way back to the Uzbek capital, via Khujand, Tajikistan’s second city and another old Khanate, but with not enough time to explore properly, we just passed through. The one thing of note we did was cross the Syr Darya, that other big river, called Jaxartes by the Greeks in antiquity, which also empties in the Aral Sea – or used to empty there, now it is being drained for irrigation of cotton in the Fergana Valley.

46. looking back: Some impressions and observations that haven’t been covered yet, during our Central Asia trip

In the end, our six-and-a-half weeks in Central Asia has become much more than our initial, 15 year old plan to do the continuation of the Silk Road. We ‘did’ the oasis cities Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand, but we also used the opportunity to see the extraordinary museum in Nukus, as well as further Russian and Soviet avant garde art works in Tashkent and Almaty. We admired the architecture, the blue-tiled mosques and madrasses, the old minarets, but also the Soviet-style ministries and theatres, the decorations in metros, the mosaics outside and inside. And not to forget, the extraordinary creativity of the people who extended their palatis – fantasy-lacking, as well as lift-lacking, half-high apartment blocks – through closing their balconies, a fascinating aspect of every Soviet-era town. We have seen every conceivable type of market or bazaar. We travelled not only the desert of Uzbekistan, but also the green hills and blue lakes of Kyrgyzstan, as well as the high mountains of the Pamirs in Tajikistan. We even crawled along the Afghan border.