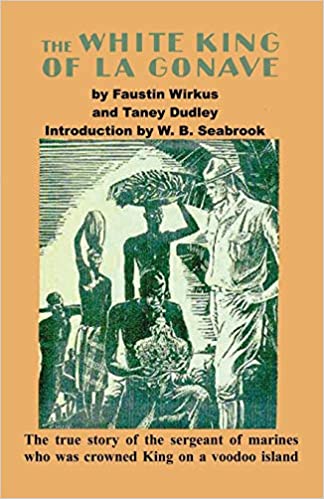

One of the most curious books written on Haiti is “The White King of La Gonave: The True Story of the Sergeant of Marines Who Was Crowned King on a Voodoo Island” (1931), by Faustin Wirkus and ghost writer Taney Dudley (I have a Dutch translation published shortly after, called “De Blanke Negerkoning”, or the White Negro-king). The title says it all: the English one a preview of what the story is about, and the Dutch one painting the inter-cultural framework of the days.

One of the most curious books written on Haiti is “The White King of La Gonave: The True Story of the Sergeant of Marines Who Was Crowned King on a Voodoo Island” (1931), by Faustin Wirkus and ghost writer Taney Dudley (I have a Dutch translation published shortly after, called “De Blanke Negerkoning”, or the White Negro-king). The title says it all: the English one a preview of what the story is about, and the Dutch one painting the inter-cultural framework of the days.

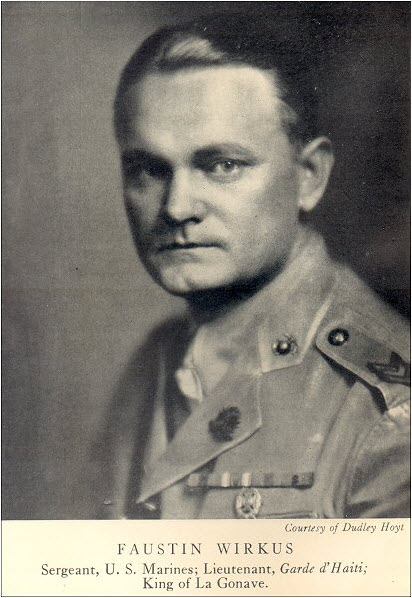

Wirkus was an American marine who went to Haiti in 1915 as part of the force that occupied the island for the next almost 20 years. Two-thirds of the book is about Wirkus’ first years, in Port-au-Prince and other stations as a sergeant and later a lieutenant of the marines, in charge of a small contingent of local gerdarmes; a time in which he demonstrates more than others an interest in Haiti’s culture – including its Voodoo religion. The last third deals with his time as a military commander and administrator on the small island of La Gonave, in front of the Haitian west coast, where he wins the hearts of the local people, and especially the various queens of the Congos, the solidarity groups, kind of collectives, with a Voodoo background.

By his own account Wirkus did away with corruption and nepotism on the island, stimulated and modernised the agriculture by bringing in new seeds and techniques, installed the necessary infrastructure, even provided medical advice to young mothers, and made himself popular in the process. To the extent that the Congos decide to crown him King in 1926, not in the least because of the incredible coincidence that his first name is the same as that of Emperor Faustin Soulouque, who ruled Haiti soon after independence, from 1849 to 1859. So Wirkus became King Faustin II, a function that came with a king’s salute from the Voodoo drums, with special flags and even a crown, and with lots of demands and requests from the local people. Only to be abandoned again three years later, after a visit from the Haitian President, who apparently stated afterwards that Haiti was a republic, that he was its president, and that there was no room for individual kings. So he had Wirkus transferred to the mainland again, where he served until he returned to the US in 1931.

By his own account Wirkus did away with corruption and nepotism on the island, stimulated and modernised the agriculture by bringing in new seeds and techniques, installed the necessary infrastructure, even provided medical advice to young mothers, and made himself popular in the process. To the extent that the Congos decide to crown him King in 1926, not in the least because of the incredible coincidence that his first name is the same as that of Emperor Faustin Soulouque, who ruled Haiti soon after independence, from 1849 to 1859. So Wirkus became King Faustin II, a function that came with a king’s salute from the Voodoo drums, with special flags and even a crown, and with lots of demands and requests from the local people. Only to be abandoned again three years later, after a visit from the Haitian President, who apparently stated afterwards that Haiti was a republic, that he was its president, and that there was no room for individual kings. So he had Wirkus transferred to the mainland again, where he served until he returned to the US in 1931.

The book is a combination of travel writing, by a young, eager chap discovering the world for the first time, and keen observation, albeit without much interpretation and conclusion, of an unknown culture, in which the observer seems genuinely interested. Perhaps against the attitude prevailing at the time, and despite the occasional racist slur, Wirkus appears to respect the people he deals with and there is little of the denigrating arrogance one would have expected from an American in the wilderness (and one often encounters to this day, too). At the same time he puts his own role into humble perspective, never really taking himself very seriously, and describes his adventures with a healthy dose of humour and self-depreciation. I really enjoyed the book, and based on my own experience with Haitian people, and he describing his, I do grant Mr Wirkus a lot of credibility.

The book was re-issued in 2015 (ISBN 978-4871872393).