Port-au-Prince combines its chaotic downtown centre with the worst of slums like Cite Soleil and charming neighbourhoods full of traditional gingerbread houses. Hate it or love it, it definetly has character.

Haiti’s capital city, Port-au-Prince, is quite chaotic. Downtown, at sea level, the streets are laid out in a more or less rectangular grid. Here many of the streets are aligned with local businesses, who operate for a significant part on the pavement, and from the ground floor arcades of the two- or three story buildings. Many street corners are being overtaken by rubbish, which seems to be a permanent element of the town, only rarely being collected – if at all. And it stinks. The most relished building here is the Marche de Fer, the Iron Market, consisting of two large iron-framed halls with on each corner a metal tower. Story has it that they were originally built in France for the Cairo railway station, but when the sale didn’t go through, the Haitian president bought it instead, in 1891.

quintessential street view of downtown Port-au-Prince: the town houses with the halleries, the taptap, the rubbish on the corner, and the market stalls in the back

In the neighbourhoods that are built against the hills the roads have a more unpredictable pattern, and invite to get hopelessly lost. This is where many of Haiti’s gingerbread houses are located, fabulous constructions with wooden balconies, window and door shutters, and steep roof spires, often from corrugated iron. They were built from the end of the 19th Century onwards, when Port-au-Prince became an increasingly wealthy trading port, and rich brokers and merchant sought to relocate from the dusty city centre to a more luxurious neighbourhood. Not all of them are in good shape; in fact, many are being taken down because it is cheaper to build a whole new stone house than to patch up and maintain a gingerbread. But luckily there are still quite a few around, not in the least the Hotel Oloffson, featuring in the Graham Green novel ‘The Comedians’, and practice and performance venue for the band RAM in the 1990s.

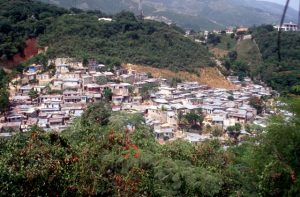

And then there are the slums, or bidonvilles, as they are called locally. In Port-au-Prince there are many small-scale slum areas, often right next to the more upmarket neighbourhoods, and they live happily together. But the bigger ones are less benign. The worst is Cite Soleil, visible from arriving planes as a vast expanse of corrugated iron shacks wedged in between the city and the coast line. Lacking any form of services: no electricity, no sewerage. Water is usually tinkered in, and sold for a small amount of money, by the bucket. Breeding ground for criminal gangs. Not a pretty place. Another notorious bidonville is Carrefour, on the outskirts of town, dissected by the motorway that goes south. And which is permanently clogged by traffic.

In fact, no matter where in Port-au-Prince, roads is almost always permanently clogged, not on the least because of the density of tap-taps, the ubiquitous cars that serve as public transport. These are generally old, battered half-closed pickups which do just that, pick up people, and, more disturbingly, drop off people, along the road. Tap-taps? Yes that is what you do when you want to get out, you tap on the side of the car, so that the driver knows he has to stop. Which is what he does, immediately. Without necessarily finding the appropriate space along the road, what’s wrong with the middle of the road anyhow? Somehow the people furthest in front are always the ones that need to get off, and it takes some time to climb over all the others, tap-taps generally being filled to the top. As the tap-taps stop in the middle of the road, this is the sign for each and every other road user to immediately try to get past, regardless of the fact that there may be traffic coming from the other side. Because the first cars coming from the other side therefor have to slow down, the ones behind them interpreted this as a tap-tap stopping, and, in good Haitian fashion, immediately start to overtake, which is easy, because there is no traffic on the other lane, well, at least not yet. It usually takes a while for the resulting mess to untangle, but Haitians do manage to get out of this again, over a period of time, with sheer steering skills, nothing else (certainly not with politeness, or with mutual understanding). A Haitian driver knows almost exactly the width of his car. I say almost, because all cars do have dents and scratches, but still, it is amazing to see them using the smallest space to slowly edge forward (never backwards, of course, you cannot be seen to lose face). Only for the ‘blokuus’ to build up again a few hundred meters further, with another passenger wanting to get out.

But also without traffic Haitians are good at blocking the streets. It is often enough that there is a group of people with a grudge, or with a complaint, or with whatever issue you can, or cannot think of, which is a reason for a demonstration. The way these announce themselves is through tall, dark smoke columns in the morning – visible from our terrace, so I know that this is going to be a day working from home. The smoke comes from burning tyres, or the occasional car wreck thrown in for good measure, which block the critical intersections in town. It is incredible, nothing works in this country, but if they decide to demonstrate, they manage to paralyse the city with excellently coordinated action, right on time, and in the right places. And then the atmosphere turns very tense: the ring leaders are not your average angry people, these are well-drilled and highly disciplined gangs that get paid to make a point. Politics is something for a leter entry, but in the past few months that point could have been delays of the parliamentary elections, delays in the publication of the results of the parliamentary elections, protest against the International community who condemned the results of the parliamentary elections, you name it. Yet, these demonstrations never last long, within a day or two they are over. Ultimately, people have to get back to work again, because somehow their families need to eat again. The poor cannot afford to idle for too long.

next: the work

And I think you like Port-au/Prince!??