Account of a seven weeks journey in the summer of 1998, following the Silk Road west from Xi’an in China to the oases in the Taklamakan Desert, and across the Karakorum Highway into Pakistan. Note that the photos have been scanned from slides, and some do need some improvement still.

(1) The Silk Road: a plan: A rough description of the geography of the Silk Road

One of the most fascinating journeys one can make is following the Silk Road, or Silk Route, that ancient trading route capturing the imagination of so many. In fact, it is not one road, but a network of trails and tracks that led from Xi’an – ancient Chang’An, China’s capital -, west through a narrow corridor between the Tibetan plateau to the South and Qing Shan mountains to the North to Dunhuang, at the edge of the Taklamakan Desert. From here, the Silk Route branched into a northern and southern arm, along the edges of the desert, to converge again at the other end, in Kashgar.

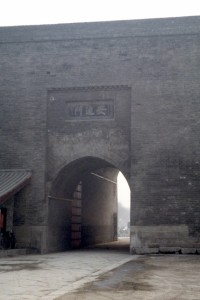

(2) Start in Xi’an: The beginning of the Silk Road was in Xi ‘an, the place known for its Terracotta Army, and its old mosque.

The Silk Road starts at Xi’an, the capital of China in the time that silk was traded. Xi’an’s history goes back to some 200 years BC, when it was founded by Qin Shi Huang, who for the first time united China as a single empire – the name China may even be a corruption of his name. He died soon afterwards, but left his marks, not only politically but also culturally: Xi’an has established its place in the world as the home of the Terracotta army, the only army that never moved anywhere.

(3) Travel to Tianshui: By train from Xi’an to Tianshui, a fairly slow, but comfortable way of traveling in ‘soft sleeper’ class.

As we had a train to catch, we did not linger around too long in Xi’an, and made our way to the railway station. We had purchased ‘soft sleeper’ tickets to our next destination, a place called Tianshui, about seven hours from Xi’an. China being a socialist country there are no classes, not even on the train.

(4) In Tianshui (1): The workings of a modern Chinese three-star hotel explained.

We arrived in Tianshui after dark, so we did not see much of the place that evening. As it turned out, there was not much to see, either, at least not in Beidao, the district where we had selected our hotel. Within minutes of us arriving in the hotel the English-speaking chamber maid was mobilised, who, within even fewer minutes, ran out of English vocabulary.

(5) In Tianshui (2): Spectacular setting of the Majishan Grottos, a Buddhist cave complex.

The reason for coming to Tianshui was the Maijishan Grottoes, Buddhist caves located some 35 km south of the Beidao district. So the next morning we got ourselves a taxi outside the hotel. Our female taxi driver was dressed in a tight black miniskirt and a black laced blouse, only the high-heeled shoes were missing…

(6) In Tianshui (3): A walk through an average Chinese city, with hutongs and temples, markets and street food.

In the afternoon we went to the other half of town, called Qincheng, which is some 20 km from Beidao. Pick up any bus that goes west, and you will be dumped in Qincheng, very simple. Next to the drop-off point was, unexpectedly, the market. Only later during our journey we began to appreciate that…

(7) Lanzhou: Sunday entertainment in Langzhou, from beach chairs and fortune tellers along the Langzou Riviera to cable cars and karaoke on White Pagoda Hill.

Entry into Lanzhou by train is depressing. It was the end of the afternoon, beautiful low sun light, but this could not compensate for the drab scenes of worn-out apartment buildings surrounding old, almost derelict factories that still manage to exhume huge plumes of dense, foul-smelling and foul looking smoke.

(8) Linxia and Bingling Si: An excursion to the Bingling Si Buddhist cave complex and the sleepy Muslim town of Linxia.

The next day we went to Bingling Si, touted as one of the four most important Chinese Buddhist cave complexes (many more than four complexes are touted as one of the most important four…). The caves are located in a spectacular setting, up a steep river valley of one of the tributaries of the Yellow River.

(9) Xiahe: About bus travel, and a visit to the Labrang Monastery in Little Tibet.

In Linxia we connected with transport to Xiahe, home of the most famous Tibetan Monastery outside Tibet, the Labrang Monastery. We missed the 09.00 am bus, the next morning, so we got on the 09.30. There is an advantage of being early, on Chinese buses, as you can choose you seat. However, when we left the bus station, we were only with six passengers, and we had the uneasy feeling…

(10) Travel to Zhanye: By train from Lanzhou to Zhanye, with views from the train window, and from our fellow passengers.

Returning to Lanzhou, we booked into a hotel near the railway station, as we planned an earlier departure the next day. As so often in Chinese hotels, we got numerous calls during the night, with offers of massage. Now there are genuine massage people in China, but when they call you at eleven at night, you can bet that you are dealing with prostitutes.

(11) In Zhanye: Some local attractions in the town of Zhanye, and an excursion to the temple and Buddhist caves of Mati Si.

We arrive in the evening in Zhanye, a mud pit after the rain, distinctly unattractive, but the next day it had cleared up, allowing a wonderful view over the snow-peaked mountains of the Tibetan Plateau. Although Zhanye has some tourist attractions of its own, the real reason to stop off here is to get to Mati Si, a small and little visited Buddhist Monastery perched against the mountains, some 60 km south of Zhanye.

(12) Jiayuguan: Jiayaguan sports the end of the Great Wall, or rather the Great Mud Ramp, and it also seems to be the last fortress of Chinese communism.

We were pleased to find ourselves in a deluxe train the next day, on the way to Jiayuguan, our next target. The carriage was adorned with carpets, curtains, and very comfortable chairs, and every so often somebody came along with drinks or food for sale. The scenery became more and more desolate, desert dominated, although occasionally we would still pass a small settlement, where people had managed to cultivate the soil around them. But beyond every green enclave the desert would be back, and the further west we went, the more ferocious the desert looked.

(13) Origins of the Silk Road: From the hunt for horses, 2000 years ago, to the hunt for treasures, a 100 years ago.

The Great Wall was built in 221 BC, to keep the barbarians out, every Chinese history book will tell you so. The Hsiung-nu – people who also gained eternal fame in Europe as the Huns, indeed symbol of destruction and barbarism -, had been attacking the Chinese for hundreds of years already. In order to find allies for his battle with the Huns, the Emperor at the time sent an envoy west, the first time somebody was to explore beyond the wall.

(14) Travel to Dunhuang: Entrepreneurship revisited, back on the tourist trail in Dunhuang.

The bus to Dunhuang, the site of China’s most famous Buddhist caves, was different from the buses we had taken so far. This was a long-distance bus, relatively spacious, and