It is time to look back at eight weeks traveling in Iran. The highlights, the lowlights and did it meet expectations.

It is fair to say that most people we told in advance that we would go to Iran, looked at us in unbelief. Were we really going to jeopardize our lives so irresponsibly, traveling to a country populated by flag-burning religious fanatics and bearded black-robed ayatollahs and mullahs insisting on women being veiled, adulterers being stoned and criminals being executed? Not that we planned adultery or any heinous crimes, but still, such a place cannot possibly be safe.

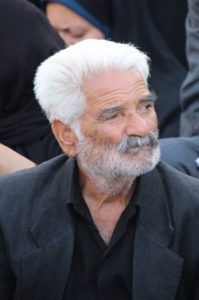

On the contrary. Seldom have I felt so safe on any of the travels I have undertaken in the past, say, 40 years. Seldom have I encountered more friendly, helpful, generous and hospitable people. Not once did I feel uncomfortable on account of religious customs in this Islamic Republic, not even during the ten days of Moharram, that quintessential Shia mourning period. From the very first to the very last day, Iranians have welcomed us to their country, to their cities.

Of course, Iran has a different culture from what we are used to in the West. Iranians are not service oriented, a taxi driver will, mostly, not lift your suitcase in the trunk if he can have you do that, instead, neither will the hotel staff carry it for you to your room. But if you ask something, the Iranian will go out of his or her way to help you; your problem becomes theirs, and they will not rest until it has been solved. Like it or not! Ask where the bus goes from, and he will walk you to the bus, and even pay your ticket. Ask wat kind of fruit that strange looking thing is, and he will make you try. Ask where the restaurant is and he will invite you for dinner.

We have a tendency to look at other, non-Western countries as a little under-developed. In the case of Iran, this is a mistake. Cyrus the Great fought the ancient Greeks, and where the Greeks are generally seen as our European cultural forefathers, the First Persian Empire of Cyrus is for the Iranians what the Greeks are for us: the beginning of a long and continuous civilization. What’s in a name? When we think of Iran, we think of those flag-burning religious fanatics. But for centuries we called this country Persia, the name the Greeks gave to the political entity that was established in the province of Fars by the Aryans, the Indo-European tribe that moved into present day Iran some 3000 years ago. And for years we associated this with beautiful carpets, poetry, mystery, romance and, not in the least, 1000-and-one nights, the cultured precursor of the rather barbaric 50 shades of grey. The truth is that Persia, which even we call Iran, nowadays, is a pretty modern country with a long, equally cultured history, where things work pretty well – perhaps even better than in Greece.

That is not to say that everything is perfect in Iran. Around each and every town, huge construction projects have been initiated, thousands of apartment buildings, most of which aren’t finished, and don’t look like they will be finished soon. Some people have blamed this on the previous government, who irresponsibly started all this, others blame it on the current government, who has cancelled much of it. Fact is that there are lots of empty shells around, or just empty steel frames. On an individual level people complain that they cannot get money to finish their own small-scale construction. Because there are no jobs: even though economic sanctions may have been lifted, the people in the street don’t notice much difference. Or perhaps this has something to do with the encouragement immediately after the Islamic Revolution of 1979, to have more children; in the 1980s each family had, apparently, an average of six children, and not even an eight-year war with Iraq is going to balance that: these children are now working-age, and jobless. Many are drug addicts, opium use having been a long-standing favourite pastime in Iran, and more aggressive drugs being readily available through imports from neighbouring Afghanistan. People complain about corruption, too, no doubt a big problem – although we have not noticed any of it as travellers in Iran -; and people complain about the inefficiencies of their government. Like everywhere, really.

Fact is that road construction is turning many two-lane roads in four-lane motorways. Metro lines in Tehran are being extended, and outside Tehran an efficient, fast and comfortable bus system connects all major and minor towns. Financial infrastructure, too, is advanced, everybody seems to have a range of debit cards which are being used for everything from paying taxis to paying fruit juice: you just hand over your card and shout the pin number to the vendor, who types it in his machine. Lots of people have a smart phone, too, Samsung or HTC; Apple is conspicuously absent, although apparently, you can get iPhones, too. Sanctions are lingering, not many American companies seem to be present, but that doesn’t seem to inhibit the economic life. Really, perhaps not everything is perfect, but this country works. Which means that, somehow, the government works, too.

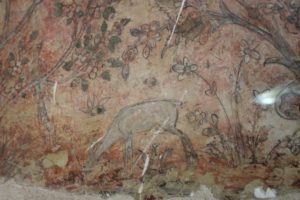

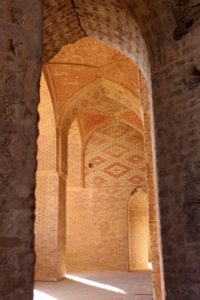

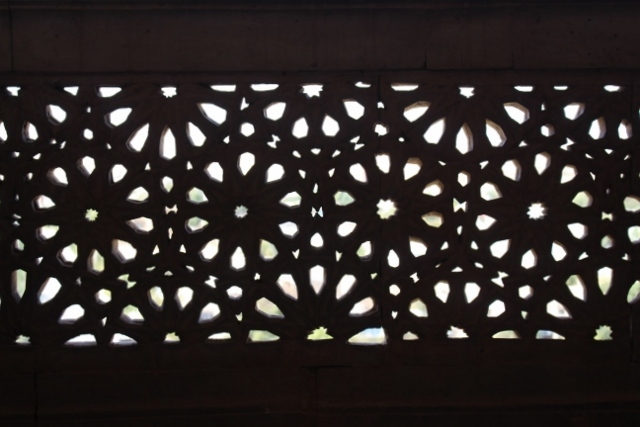

Expectations, then. In the eight weeks we travelled we encountered no lowlights, not one. In terms of natural beauty, perhaps slightly disappointing, although this is likely related to the time of the year we travelled, September/October, after the scorching hot summer that has turns everything green into yellow and brown. But the desert is beautiful all year round, and the Alborz and Zagros Mountains provide spectacular scenery, if perhaps even more attractive in Spring time. Architecture?

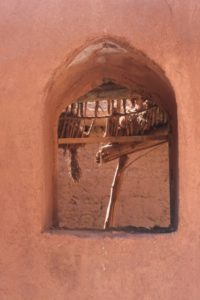

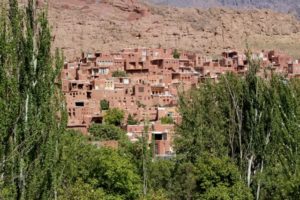

Fabulous, and great variety, from the ancient columned ruins of Persepolis and century-old mountain villages to arched bridges, vaulted mosques and ostentatiously decorated 19th and 20th Century palaces and merchant houses. It is just a pity that most of today’s building is rather tasteless, functional rather than aesthetic. Isfahan is perhaps the foremost destination if it comes to seeing the sights. Yazd, with its narrow alleys in the old town, is another must for the visitor. But for the real Iranian atmosphere, smaller, less touristic towns perhaps provide more of a local taste, and more of that typical Iranian hospitality. Tabriz comes to mind, and Sanandaj, and Bam. And we had our most hospitable encounters in Kermanshah – it depends on the moment, on the people you meet.

But the Iranians themselves definitely surpassed any expectation we had.

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts