Earlier I mentioned a third area of interest, beyond Central Riga and Old Riga, and this is the area south of the Old Town. Here is the Central Market, a sprawling complex covering five huge German-built halls to store the infamous WWI zeppelins. When the market was moved to its current location in 1930, the government decided to bring in those hangars from elsewhere in Latvia, which now form the heart of what is claimed to be the biggest market in Europe; it may well be, with each hangar being dedicated to one or two categories, which easily spill over to stalls outside, in between the buildings. Colourful, and mostly smelling great. All those mushrooms we have seen in the forests are being sold here, but also enormous quantities of fish, smoked in all different ways or just raw. Vegetables, and especially berries, it is the season; red and orange raspberries. And the widest selection possible, I think, of vicious sweets, in the most vicious colours.

Behind the market is the Academy of Science tower, mostly relevant because from the balcony of its tower you have another fabulous view over the city, albeit only at 65 meters, less than the church tower in the Old Town. The building itself, the first high-rise in Latvia, with a total of 21 floors and 107 meters high, was completed in 1961. The view also includes the TV tower, claimed to be the third-highest building in Europe with its 367 meters, and the National Library, on the other side of the Daugave River, an attractive modern building.

Just behind the tower is the Lutheran Church of Jesus, the largest wooden church in Latvia and one of the largest wooden churches in Europe. As wooden buildings go, they tend to burn down from time to time, but this one has lasted from 1822, and looks in prime condition. Unusually, the inside church area is round, and has a fabulous acoustic in the middle.

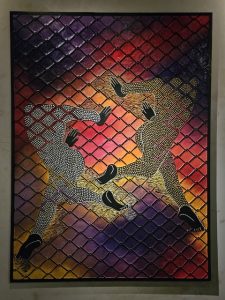

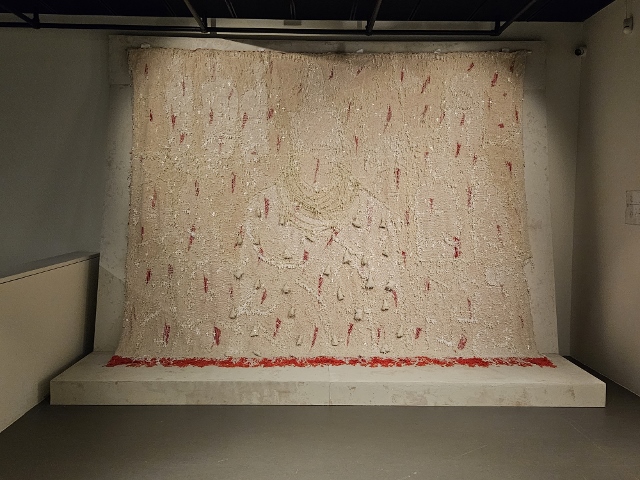

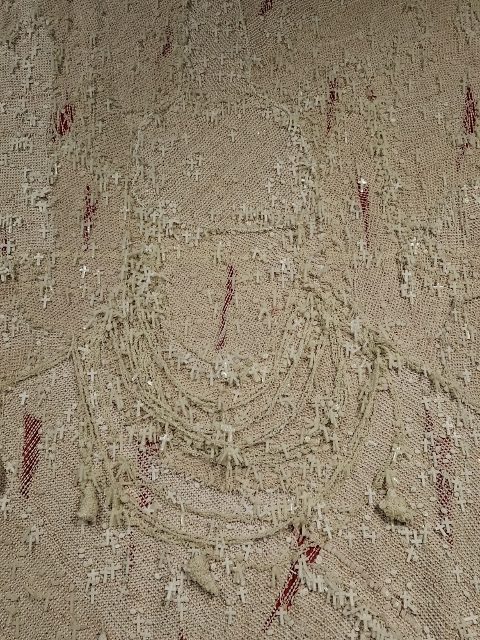

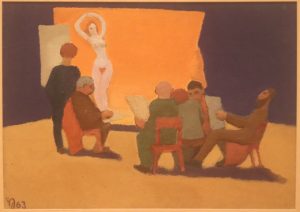

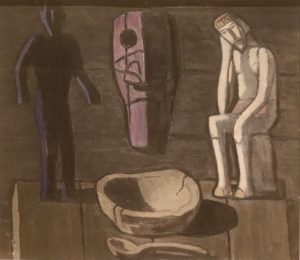

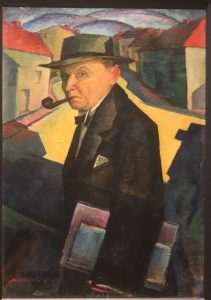

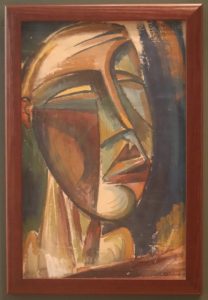

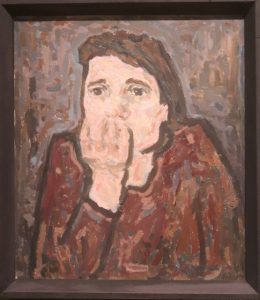

We also run into the Lastadija artist collective, or so I think. We were looking for a big fox on the wall, which we actually spotted from atop the tower (!), and when we arrived in the courtyard with the fox, this turned out to be a sculpture garden cum coffee bar. And at around 1 pm they also serve lunch, great vegan curry and rice, for a donation. Absolutely wonderful place, very nice people, and great art beyond the fox. See, these are the surprises Riga offers, also outside the Old Town.

The one thing you don’t read in the tourist guides or websites is that Riga is also a vibrant city. There are people in the street, walking, or on terraces and in restaurants. The city is alive – admittedly, it is very pleasant autumn weather, but this was also the case in Tallinn and Tartu, and in Helsinki, yet these were comparatively sterile places, without much atmosphere. Riga is buzzing, even on a weekday evening.

On one of those evenings we met up with an old Latvian acquaintance, from long ago. He explained that this split between locals and ethnic Russians, also evident in Estonia earlier, is actually much more complex than it looks. Nationalists like to focus on language, if you speak Latvian, you are one of them, but our friend has a Russian mother – who is very critical of what happens in Russia and feels more connected to Latvia -, and a Latvian father, who more and more leans towards Russia, because everything was so much better in the past, in his eyes, and Russian empire resurrection could bring that back. He also points out that Latvian nationalism is a fairy recent thing, which, however, is being complicated by the fact in the in the Middle Ages, before Russian domination from about 1800 onwards, the north of Latvia was mostly associated with Swedish power in Estonia – staunchly Lutheran protestant -, and the southeast with the Lithuanian-Polish entity of that time. Staunchly Catholic. Only the southwest was a somewhat autonomous region, called Courland, which, incidentally, is still proud of its past colonies, an island in the Gambia River in West Africa and Tobago Island in the Caribbean. I told you, I am learning my European history as we go.

Next: a little more on the Baltics history. Or just continue the journe, to the bog.