Thousands of years of history are exposed on the way to Ruse, from Roman settlement and Middle Age rock churches to 19th Century and Soviet-style architecture.

The Bulgaria part of our trip – the shorter half of the trip – is coming to an end. We are heading to Ruse, on the Danube, to cross back into Romania.

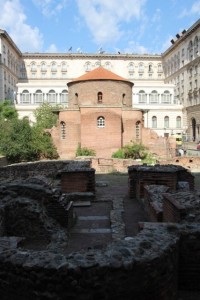

On the way, north of Veliko Tarnovo, are the ruins of an old Roman settlement, Nikopolis-ad-Istrum. Nothing like the impressive complexes of theatres and temples along the Turkish coast or Lebanon or Jordan, no, just a small, well laid-out settlement, well explained, too, as to get a good overview of how a Roman town looked like. Tasteful, not over-restored, the pieces of wall remaining are clearly original pieces of wall. Very peaceful, too, this site. Worthwhile the detour.

Another interesting feature towards Ruse are the rock churches, established in the karstified thick limestone formation that forms the basis of the Rusenski Lom Nature Park. These churches have not been hewn out of the rock, I think – not like the rock churches of Ethiopia, for instance – but have probably used existing caves, perhaps a little adjusted. Apparently, there are some 40 churches like these, of which the Mother Church near the village of Ivanovo is one of the most famous, sporting frescoes dating back to the 14th century – amazingly clear and bright, still, and according to the caretaker not restored, but ‘maintained’ over time, whatever that may mean. The church is an easy 10-15 minute stumble-uphill from the parking lot, but what is more, a little further is Panorama Rock, providing a spectacular view of the surrounding mountains from high up, and providing an equally spectacular picnic spot.

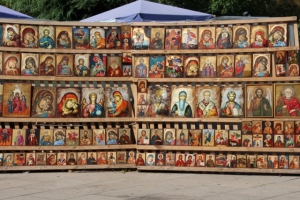

Ruse itself is a laid-back town, at the Danube. The centre is formed by a huge square, from which no less than 18 streets radiate out. One of them leads to the red-coloured Opera House, and the Sveta Troitsa church, remarkable because it has been largely built below ground level. An Ottoman rule in the 17th Century determined that churches should be as inconspicuous as possible – but at least they still allowed churches to be built. The square itself, and nearby streets, are lined with fairly attractive houses from end 19th Century, including the Profit Yielding building, occupying a full side of the square. This structure was designed by a Viennese architect to hold a theatre as well as several other rooms and halls, meant to be rented out to earn money, with which local schools could be funded – which explains the rather unique name (I wonder whether the name was maintained throughout the communist era, and whether the principle is maintained today: from the fancy restaurant terraces that now operate from the building quite some education could be supported). The other ominously-present building on the square, housing the municipality, is quite a bit newer, one of those Soviet-style 1960s constructions built with little fantasy – in itself a gem.

And so is the local hotel where we booked a room, the Grand Riga, another one of those 1960s monstrosities, overlooking the Danube river. However, we receive an upgrade, and are put in a really nice, recently refurbished room on the 10th floor, with great modern furnishing, and even greater views – it is just that not all of the hotel has been reconstructed, yet, the water of the shower and the bath is lukewarm, and the breakfast the next morning meagre, to say the least, with as absolute lowlight an impressive-looking expresso coffee machine that dispatches instant coffee of the more horrid quality.

Time to move on, perhaps?

Next: reflecting a little, in the Bulgaria experience

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts