There are several shrines in Shiraz; the ones we visited were, at least for us, the uninitiated, a rather underwhelming experience.

In the long history of Shiraz quite a few people have died here. Some of the more famous ones have been buried in elaborate tombs, that attract both religious and secular pilgrimage.

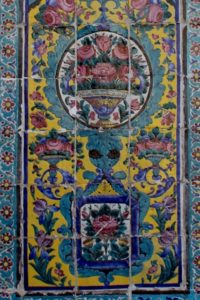

Firstly, there is the Aramgah-e Shah-e Cheragh, the shrine for Sayyed Mir Ahmad, who was murdered here in 835 AD. Sayyid was one of the 17 brothers of Iman Reza, the 8th of the 12 Imans that define Shiism, and his shrine is somehow one of the holiest sites in Iran. The current mausoleum is fairly recent, and not particularly beautiful: as so often, size matters more than taste. Men and women enter through separate entrances, but once inside, we are happily united again in huge courtyard, which flows over into a second one. Lots of people are sitting on large carpets, in front of the actual mausoleum; others put their shoes in plastic bags, and enter the building.

and outside the complex, the short translation of Ayatollah Khameini’s letter – but very unlike the Iran we have so far experienced

Because we are foreigners, we are to be accompanied by somebody from the International Affairs Department. And because we are foreigners, we are actually not allowed inside the mausoleum, not allowed near the tomb. Why not, the lady from International Affairs couldn’t tell us; last week there was no problem. Now do I have very little with tombs that are subject to adoration and pilgrimage, but banning non-believers is not going to help promote tolerance and understanding. She did treat us to a letter from Ayatollah Khameini, though, who felt the need to address the ‘youth of the West’ after the recent terrorist attacks in Europe, which, naturally, are to be blamed on the US and on Israel, with Muslims being a disproportionate victim of terrorism. Coincidence or not – probably not -, a little outside the complex was a large banner, ‘Down with America’ and ‘Down with Israel’. We haven’t seen any of this yet in Iran (except in Tehran, at the former US Embassy), and seldom felt any hostility against the West – on the contrary. Perhaps there is some discrepancy between the official anti-western line, and the vast majority of the people?

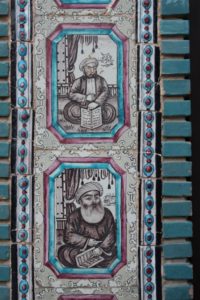

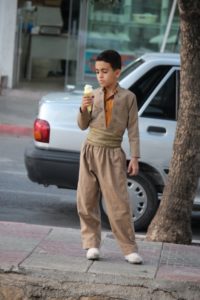

Anyhow, up to the next tomb, that of Hafez, one of the most respected poets in Iran, who died in 1389 AD. He has been buried somewhere in the north of town, walkable distance from our hotel, but it is already hot, so we decide to take a taxi. Shiraz has a mostly one-way system, but that does not stop our taxi driver from backing up for hundreds of meters, against the traffic, to save from driving around. He then skips a red light, turns into another one-way street, against the traffic, and after turning at the end, into a two-way street this time, speeds whilst overtaking on the left lane, ignoring oncoming traffic. Next time, we walk again.

Or better even, next time we skip the tomb business all together. Hafez’ tomb was another disappointment. After having paid a relatively exorbitant entry fee, there is really very little inside, apart from a tomb under a small, new pavillion in a not very attractive little park. The importance of Hafez to Iranian people is obvious, many stand around his grave, moving their lips and silently reciting lines from his poems. But for me, I don’t have the spiritual connection, and without it, there is very little left. I have a look in the bookshop: if there is ever a moment that I will read some of Hafez’ work, it is now. The shop has an attractive volume with his poems, in both Farsi and English, but the English in this 2015 edition, although perhaps not from the early Middle Ages, is still very old-fashioned, not something that easily reads away. Missed opportunity, perhaps?

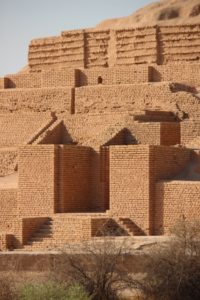

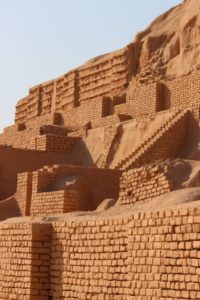

We are running out of options. But there are a few tombs left, outside Shiraz. Those are the tombs of the rulers of the First Persian Empire, the Acheamids. Near the ruins of Persepolis.