Voronet Monastery, painted in Voronet-blue, contains one of the most famous external frescoes of all Bucovina Monasteries, and there is a look inside, too

The Voronet Monastery is one of the older ones, built in 1488 at the initiative of Stefan the Great, as a token of gratitude for Daniil the Hermit, who “advised (Stefan) in a time of distress” – likely to refer to yet another battle with the Ottoman Turks. The building has a tower, and several external additions dating from 1547.

The key fresco here is the Last Judgment, covering an entire wall, and still in excellent condition. There is no doubt that blue is the dominant colour in this church.

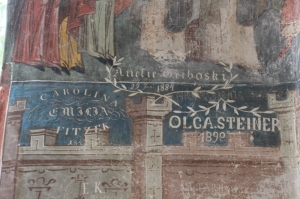

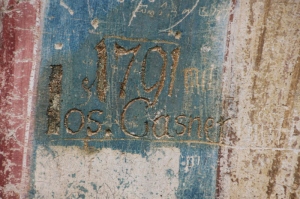

Sneakily, I managed to take some pictures inside, too, just to be able to share the fabulous quality of the inside decorations of these churches, too.

The other monasteries included here are Humor, Moldovita and Sucevita. See also ‘the painted monasteries of Bucovina‘.

RSS – Posts

RSS – Posts