Drab Quba, in the Northeast of the country, contrasts sharply with the mountain village of Xinaliq, amidst spectacular scenery.

The most beautiful scenery in Azerbaijan, or so they say, is east of Quba. And the prettiest village, Xinaliq, also happens to be east of Quba. Our next destination is a no-brainer.

Especially because our proverbial luck struck again. The evening before we were to leave Baku I found the name of a man who can arrange day trips to the mountains, from Quba. So I sent him a message, only to find out that he is in Baku, and will go to Quba the next day. Do we want a lift? Well, yeah, why not? Then it turns out that he was in Baku for a golf tournament, he is actually the director of the Azerbaijan National Golf Club in Quba. Being keen golfers ourselves, something like that creates an immediate click.

We arrive in Quba halfway the afternoon, plenty of time for a stroll through town, even though it has turned cloudy. More than plenty off time, we find out, as our walk through Quba is probably one of the most uneventful things we have done in any of our travels. The town is utterly boring, the only people on the street are old men, who mostly avoid eye contact and only occasionally manage a ‘salaam’. Most houses are low rise, many are run-down. The only entertaining parts are the various balconies, wooden frames and windows – equally run down – and the decorated metal tops of the downspouts. A mosque of uncertain age, a small park, and steps to the bridge across the river, that separates one half of town from the Jewish neighbourhood. Which is slightly more upmarket, some newer, and quite ostentatious houses, but in between the same run-down dwellings. And equally few men in the street, who murmur ‘shalom’ instead of ‘salaam’.

The only notable construction in Quba is the Genocide Memorial monument. From 30th March 1918, for two months or so, Armenian militias went on a rampage, and killed thousands of other ethnicities, of which the majority were Azeri. Estimates range between 10,000 and 50,000, mostly in Baku. But the Quba region was also a victim, proof of which is an in 2007 discovered mass grave: one reason to put the Genocide Memorial, completed in 2013, here. As always, it is difficult to find out what exactly happened and what is nationalistic banter. One of the most reliable regional history books only spends a paragraph on the issue, without numbers, suggesting that on the whole this was actually a minor issue in the violent early 20th Century years in the Caucasus. Whatever, the Memorial itself is a very tasteful – if that is the right word – construction of two opposing white pyramids, which form the entrance and exit of the underground exhibition, rich in old photographs of people from the area, and of damaged houses, to be sure. Outside a number of rows of black granite pillars of differing heights have been placed under the apple trees, reminiscent (the pillars, not the apple trees) of the Holocaust monument in Berlin. Very impressive, and as so often in modern Azerbaijan, aesthetically pleasing.

The mountains, then, and Xinaliq. Our golfing friend had arranged for a car and driver, and indeed, the next morning a super-duper extended Lada Niva appeared, the Russian answer to the SUV, with the friendly, non-English speaking Micmeth. The extended part of the Lada referred to the large trunk at the back, the passenger area was still awkwardly small to climb into and out. The Lada remains an extraordinarily basic car, with an interior – and windscreen wipers – not much different from my first VW Beetle, 40 years ago. Except that there were seatbelts; but no clip to fasten them, they are just for fooling the police. But Micmeth was obviously happy with his car, and it did what it had to do.

The weather was overcast, but still dry. Because of the language barrier conversation remained a complex issue, with a bit of English and a bit of Turkish, so at every stop on the way it was a surprise again what we would find. The first one required a short walk, and when we heard water flowing, we already expected it: a waterfall. And indeed, a hundred meters further on a tiny stream came clattering down, so much even that we felt the spray. Only after we walked away again, and the spray stayed, we realised that it had started raining. Hmmm. What about that mountain scenery ahead of us?

But the clouds cleared, and not much later we crossed a pass into a next valley, in bright sunlight. And then the mountains are, indeed, spectacular. Not much vegetation, but enough for enormous herds of sheep to move slowly around, sometimes in the wide riverbed to drink, at other times climbing the slopes searching for the last green grass. Big dogs, a bit like the Anatolian sheep dogs, and men on horses keep the herds under control, although they can’t prevent them from crossing the road occasionally. A rather hazardous practice given the average driving habits of the Azeris.

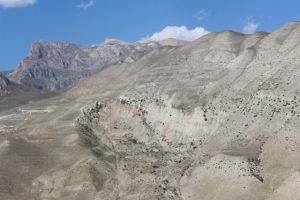

Along the way, the occasional village stuck against the mountains. Little, glistering streams that come down to join the main river. Distant peaks that even contain a little snow, as late as September. And then, finally, Xinaliq, perched high up a hill. This is, according to some, the highest village in Azerbaijan, according to others even the highest village in entire Europe, at 2335 m. The local historians claim that the villagers are descendants from the Caucasian Albanians, an early Christian kingdom that has vanished under the Arab conquest. Perhaps; there are more claims to this descendancy, and very few reliable traces.

The village is a curious mixture between stone walls, often attractively built with zig-zag patterns, and corrugated iron. It is no match for some of the picturesque villages we encountered several years ago in Iran, but it does have a certain charm; steep unsurfaced paths, some wide enough for cars, littered with droppings of sheep and cows, wind in between seemingly randomly placed houses. Cow dung patties are being dried against the sides of the houses, briquettes of the same fuel are stacked as low walls, in preparation for the winter. Chicken and turkeys skitter away, children on the other hand are attracted by us visitors; but always respectful, no begging for money or pens or sweets, just a timid ‘hello’. Tourism hasn’t spoilt this part of the world yet. And indeed, there are hardly any other visitors, and most of them we know from our hotel. We enter the tiny museum, one room only, with real old carpets and saddle bags. We wander around through the village, up to the top, and back down again. From the smell it is obvious that this place doesn’t benefit from oil; no sweet crude here, but the scent of smouldering cow dung. And we have lunch at a homestay, wonderful home-cooked food, but with the familiar trappings of the homestay concept: very limited conversation, not from unwillingness but from lack of shared language.

But overall a great experience, lovely people, intriguing village and beautiful landscape. Makes us almost forget the most uneventful walk of our travels, just 24 hours earlier.

On the way back to Quba it starts raining again.

next: to the surreal exclave of Nakhchivan