Our first cross-country trip over the mountains, and what a trip it was, with lots of snow-capped peaks, lots of animals on the move, and lots of yurts and lakes.

The Pamir Highway proper starts in Osh, the same town we had been arriving from Uzbekistan some two weeks earlier. To get there, with car and driver, takes two days, through some of the most spectacular countryside we have seen so far on this trip – although I suppose the term ‘spectacular’ perhaps alternated with ‘awesome’, ‘beautiful’, or just ‘woh’, linked to countryside, may occur more often in the weeks to come!

After an hour driving parallel to the Ala-Too, the mountain range south of Bishkek, – and after having spotted no less than four Lenin statues, each village seems to have one; what is it with these people and Lenin? -, we turned into a valley, and started climbing along the fast-flowing Kara-Balta river.

The valley soon reduced to a gorge, with steep sandstone cliffs on both sides, and ever dryer landscape. Every so once in a while we had to slow down to negotiate herds of sheep, and horses, accompanied by horsemen, on their way to summer pastures on the other side of the mountains. There is a well over 3500 m pass, but all traffic, including horses and sheep, nowadays take the narrow, dark and damp Too-Ashuu tunnel, at 2564 m – which is a pity, of course, from a panorama point of view, but we had no complaints, nonetheless. Everywhere snow-capped mountains, yet with every corner changing scenery, and somehow never boring.

herdsman on horseback, managing large flocks of sheep that have a habit of getting in the way of cars

The tunnel was closed for a while, because a group of horses was going through, and this gave us an interesting insight in the way Kyrgyz drivers operate if there is no police around. Those disciplined, careful chauffeurs of cities and highways now scramble for position, to be the first to get into the tunnel as soon as it opens again, ultimately lining up four rows thick. Reminds us of the Chinese. The sheep and horses we had passed on the way up now caught up with us, and the many other cars, again, including some horses who travel first class, in the back of a truck instead of walking.

When we finally got through the tunnel, we entered yet another landscape, a pretty arid valley, no trees, just grass – the summer pastures. Apparently, this valley is entirely covered with snow and ice in winter, when there is nobody, except on the occasional rudimentary ski slopes. But come summer, animals and people start gathering again; plenty of animals had already arrived, and were grazing happily, and many of the Kyrgyz shepherds had arrived too, and had pitched their yurts, and their wagons – the modern-day yurt alternative for nomads, who travel with cars as well as with horses – along the road, or along the river a little further away. They come every year, and they come to the same place, still lined out on the ground with white-painted stones.

the valley of Bala-Chychkan is full of honey boxes, even trailer mounted, something we have seen earlier in Romania

The valley is at around 2200 m altitude, and to get out, we climb to the Ala-Bel pass, at 3175 m, before descending again in the direction of Osh. We stopped for the night in a place called Bala-Chychkan, no more than a couple of halfway guesthouses, really, catering for the people that do, like us, the Bishkek-Osh road.

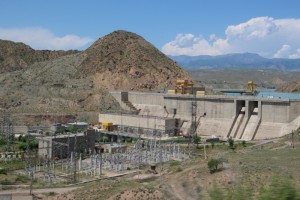

Just past Bala-Chychkan is Lake Toktogul, one of several artificial lakes in the Naryn River, that generate cash for Kyrgyzstan from hydro-electricity – and headaches, too, in the form of international conflicts with many of the neighbouring countries, downstream from Kyrgyzstan’s rivers, who rather want the water, for their intensive irrigation of cotton fields. Although it is end of May, high tide from the melting snow in the mountains, the lake is pretty low, and according to our driver has gone lower and lower every year, so the water must go somewhere. The lake, and the two or three following ones, provide us once again with a different landscape, not so much snowy peaks anymore, as we are much lower now, but plenty impressive steep red and purple sandstone gorges alternating with more expansive views once the valleys widen again. In the narrowest parts some of the sheer rock faces opposite the road resemble a level five Sudoku for structural geologists.

But after a while the mountains peter out, and we enter the flat, or at most mildly undulating, Fergana Valley, the extension of the valley that we crossed in Uzbekistan. And the scenery changes once again: no more herding cattle, but agriculture, people working the land growing crops, including rice. The change from the nomad Kyrgyz back to the settler Uzbek.

For a while we are driving next to the border with Uzbekistan, a 15-20 meter strip of no-man’s land in between two barbed wire fences – in the past, the road to Osh would just go straight, through Uzbekistan, but now, with strained border relations and complex visa requirements, we drive all the way back in to Jalalabad, before turning back to Osh again. A long, and by now rather less attractive part of the journey, but nonetheless the end of a fascinating two days of Kyrgyz landscape. And we haven’t even started on the Pamir Highway yet!