There is not much in Nukus, the capital of Karakalpakstan, except for the State Museum of Arts. But what a museum it is, full of once-forbidden Russian avant-garde art.

Karakalpakstan isn’t the most exciting part of Uzbekistan, its capital city Nukus is – hopefully – also not the most exciting town. But it has one unique feature: the Nukus Museum, short for the “Karakalpak State Museum of Arts named after I.V.Savitsky”.

In the 1950s Igor Savitsky, a artist-painter working from Moscow, joined an archeological and ethnological excavation to Korezm, a historical site in Karakalpakstan. He attached himself as the expedition’s artist, but soon also began to collect artefacts, carpets, utensils and local art works. After the expedition had finished he stayed on in the region, and managed to convince the authorities to set up a local museum – which was opened in 1966, with Savitsky as director. The ethnological section was soon joined by a Fine Art section filled with work of local artists, greatly who had been greatly encouraged by Savitsky. So far nothing out of the ordinary, and nothing worth coming to Nukus for, with all respect.

But then Savitsky somehow also managed to access the huge amounts of Russian avant-garde art of the early 20th Century, much of it banned by Stalin as anti-revolutionary, or formalist, or bourgeois, or anything else that did not stroke with the ideas of the Soviet regime. All these forbidden works had been hidden from view – begging the question how Savitsky knew so much about it, but never mind -, in museum vaults, or in the attics of out-of-favour artists or their surviving relatives. He went on to build an enormous collection, estimated at over 50,000 works of art – paintings, sculptures, drawings, sketches, collages – by arguing with museum directors and convincing relatives to part with the works, occasionally paying for them. Paying with state funds, to be sure, because the amiable Savitsky also managed to access public money for his hobby. It has been suggested that the authorities went along because Nukus, where the collection was to be housed, was about as remote a place as one could imagine in the Soviet Union, but this does in no way diminish the achievement establishing this extraordinary collection, and displaying it, too.

Savitsky died in 1984, but his museum continued in the relative obscurity of Nukus, until with the break-up of the Soviet Union in 1991 the world slowly started to learn about it, attracting increasing attention, and with it, increasing amounts of money. Currently, only some 2-3% of the works can be displayed in the museum, but construction is underway to enlarge the exhibition space.

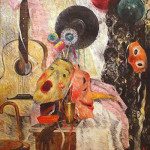

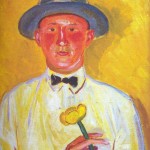

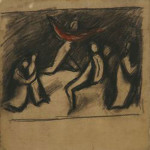

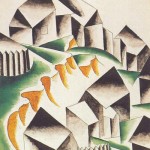

We weren’t disappointed. Although we were initially directed to some exhibition of local artist, nice enough but again, not something one comes all the way to Nukus for, we ended up on the third floor, which is where the real thing is, an overwhelming amount of paintings, but also drawings, water colours, gouaches and sketches, from the 1920s and 30s. Somehow, Kandinsky and Chagall haven’t made it to the museum, but there is so much to enjoy, so much I wouldn’t mind hanging on my walls at home. Fabulous (that is, if you like this type of art, and luckily we do). Never seen anything like it, and we do visit other museums and exhibitions, so once on a while. Yet, I wonder how long the museum will be able to resist monetising part of the collection, in this poorest of ex-Soviet corners of the world. From tourism alone the people won’t survive, here.

The Collection

Although photography is prohibitively expensive in the museum, I did pay the fee, and took hundreds of photos, which I will work into a gallery some other time in the future – unfortunately, there isn’t much of a catalogue, and what is available, is in Russian. Below I have given a few examples of the works, drawn from the museum’s website. Which also gives some interesting reference to the artists, and the hardship they had to endure based on their being avant-garde artists. Many of them did not die a natural death. Lev Galperin was arrested in 1934 accused of producing counter-revolutionary paintings and depicting the Soviet leaders disrespectful: five years imprisonment ended with “execution by shooting”. Vladimir Komarovsky, a well-known icon-painter, was arrested several times, the last time, in 1937, for being part of a Counter-Revolutionary Illegal Monarchic Union of Church-goers, refused to plead guilty, and was shot. Vasily Shukhaev left Russia in 1920 to travel to France and Morocco, only to be arrested for trumped-up espionage charges when he returned 15 years later. He actually survived the correctional labour camp. Others were sent into exile and never heard from again. And many somehow accommodated to the system, and kept working in promotional campaigns, designing posters and book illustrations, or as restorers of approved master pieces. Whatever they choose, or whatever was chosen for them, most didn’t develop their artistic skills much further after the 1930s.

What is left – probably only a fraction of what has been produced – is definitely worth seeing, though. Nukus Museum, highly recommended.